Commentary

-

Reading Commentary

In Temporality and the Multimedia Archive, Wolfgang Ernst

In In Temporality and the Multimedia Archive, I appreciated Ernst’s thoughtful take on media archaeology – the field of function and poetry through digital archiving. I also believe that the form of a digital archive greatly informs the content showcased. He also discusses the dynamic nature of these spaces, an active archive rather than a static one. Archives these days are can also be increasingly banal, and provides a larger overview of a person or era, rather than an interest in every separate artifact. More than data back-ups or clones of existing sources, they are authored by the archivist, who should consider a variety of user experience types. While his content is interesting, his writing style is not very accessible and could be simplified to push forward his claims.

-

Memory and the Archive

The three chapters in “Digital Memory and the Archive” by Wolfgang Ernst brought out some very interesting ideas, even though I’m not familiar with some specific words. But the whole idea is that Archive has become a new dynamic method in digital media Vs. traditional archive. And in dealing with art, music and video, the digital archive need to focus on the aesthetics inherent. And also the author argued about the temporarity of storage memory in modern technology. The computer as archive part reminds me of the transformation of modern computers. Different from the concept the author addressed here, I found it more interesting to see how can people archive the experience of using different computers in different stages. When I studied the game design class, the professor chronological showed us different games and the computers which represented that age. Computer as significantly artificial product is also worthy of being documented and represented.

-

Assignment 10: Digital Memory and the Archive

Assignment 10

#Temporality and the Multimedia Archive According to Ernest, temporal ontology offers a way to understand how all computer-based, calculational media are temporal or wordly, and this forces us to rethink the spatial emphasis of older regimes of memory. He also emphasized the temporality to the multimedial archive. If computer-based, calculational media is more worldly than the older version of media, then it should be more prevalent, multicultural, and more inclusive. The multimedial archive is wordly in the sense that many people can access this storage and its vast amount of knowledge for free (or almost for free). However, I wonder if that is true. Those in charge in the technology and possess the mathematical knowledge definitely have more influence in the platform of multimedia and its archive. Their influence is subtle and often not visible to the layman.

#Underway to Dual System It deals with the archiving of media artistic work but opens up to a wider ontological question of what the media are in the age of technical media. The author discussed the answer to the question by paraphrasing George David Birkhoff’s speech which emphasized that “aesthetics is, quite simply, about a “ratio of order and complexity”. This definition of aesthetics is very specific to archiving science-based art since it is technical and mathematical. This idea also raises the question about how to quantifies order and complexity and whether there are multiple standards for such measurements. Overall, Earnest raised questions about the practicalities of archiving science-based art and the ontology of media.

#Archives in Transition Ernest’s idea is that the archival order gives way to archival dynamics and the control structures specific to that. He also raised the question : does the archive become metaphorical in multimedia space? This question is not about the understanding of archive but also about the whole range of media that is related to visual culture and interface studies. Basically, if we fail to address the time-critical, technomathematical modulation of what comes out as the almost like metaphoric surface effect, we fail to understand where power lies in contemporary culture. To parse Ernest’s confusing expression, I have to reread multiple times. So archival order is the result of time-critical, technomathematical modulation. If we understand this order, then we can understand the dynamics and control structures that involve a whole range of media, visual culture and interface studies. This idea is reasonable for mordern archives since they are more likely to be time-critical and technomathematical than conventional archives.

-

Digital Memory & The Archive

In Temporality and the Multimedia Archive, Ernst’s arguments and contemplations in Underway to the Dual System and Archives in Transition are introduced. It seems that both will discuss archiving of new digital media and the dynamics that stem from the inherent differences in digital vs. analog artistic works. In Underway to the Dual System, I thought an interesting argument being made was the idea that an archive was on longer defined by it’s content but rather it’s connections and how the content is linked. I think this idea doesn’t necessarily work completely when you think about the ephemerality of web-based media and the whole purpose of Internet archives that we discussed this week. Later in the chapter, they go to refer to the Internet as a “transarchive” and I believe this distinction allows their previous argument to breath. I thought the sentence “what makes the difference between a memory and an archive is an organized archive barrier” was very interesting. It was really interesting reading Archives in Transition in a time where we’ve had high speed internet and streaming media for enough time that it’s ingrained in our society. While reading this section, I had to take a step back and recall a time when transmission media was non-existent or a novelty.

-

Digital Memory and the Archive

Wolfgang Ernst’s essays on Digital Archiving is an interesting look at technology and media archaeology, and combines a lot of poetics about the physicalities and functionalities of digital archiving with analyses of temporality and archives.

The introduction of time into archiving, and how that adds a new dimension to the world is interesting. Most notably, the idea of Wikipedia being an archive that is permanently dynamically rewritten, instead of having a permanent read-only, is an important distinction. The idea of the archive, then, can be considered differently (and Ernst even considers everyone’s computer a kind of archive), and we can look towards these media objects to understand, in the same way that we use archives now.

My main concern with Ernst’s essays, is that there seems to be a lot of terminology and figuring out the ontologies of these digital archives. While there are cool and interesting comparisons that relate the physical functions and hardware to its semiotics, I had a hard time piecing together the arguments, for example, the movement from “emphatic cultural memory” to “intermediate media memories.”

-

Digital Memory and the Archive - Kelly

The reading illustrates different ways in which the establishment of digital archives is not only about translating and transferring existing material into digital form and constructing a digital framework and interface, but instead allows as well as necessitates rethinking of archiving. How new technologies have, and will, affect and shape the ways in which we conceptualize and treat memories is also alluded to.

The digital world, with its binary units, intrinsic linkages, and transitive nature, is undoubtedly very different from traditional means of storing and archiving information. These differences offer new advantages and perspectives, but also introduces new issues to solve and deliberate on. The transitive nature of digital information and communication is especially inconsistent with the very notion of archives, as previously and perhaps presently still established. While it felt logical to assume that digital archives are more durable or reliable than the physical, after last week and this week’s readings, this idea has definitely been well challenged.

-

Digital Memory and the Archive Commentary

Ernst’s writing, or its translation at least, seems to focus more on aesthetics than on practicality. All three essays share complex terminology and a generally confusing structure. Like others, I found the text to be a slow read because of this.

The essays focus on the structure of digital archives as opposed to the material contained within. By considering the nature of the digital archive, Ernst takes an interesting approach to studying new media. He emphasizes the dynamic nature of digital archives, and argues that they constitute new “cybernetic beings.” While archives can take on many different forms, especially in the digital age, I wonder if this is an extreme view to take.

However, I do agree that modern day archives are both less static than those in the past and subject to mathematical principles. Because of this (and general curiosity) the notion of aesthetics as a “ratio between order and complexity” was striking. The archive as new art idea is one that could be extended to include multiple technological systems.

-

Digital Memory and the Archive AD

Thoughts

It is suggested that digital archiving must be done on demand, essentially such that it “archives itself”. The internet is described a new, dynamic type of archive: a “transarchive”. Analog storage media is praised for having a higher quality and shelf life compared to digital. I thought it was interesting that it was suggested that some information or art might be transient and “instantaneous” in nature and thus shouldn’t be archived. Archives in Transition explores how the aesthetics of storage are changing radically with digitization.

-

digital archive

In this article, Wolfgang takes Europeana as an example to illustrate on how new archives respond to current needs rather than just being a read-only memory or Data backups, which responds to their behavior. For now, what we try to do is to archive the traditional art. While new media art nowadays also gives more attention on interaction between audience and the artwork. I wonder what would happen several decades later when we begin to archive new media art which itself could already be interactive with users. Take team lab as an example, most of Its artworks change based on the presence or behavior of viewers. When we archive them, how can we use an interactive way to capture the enhancement of this exaggerated user-experience? Maybe at that time, the filters on a digital archive’s website are not only limited to color, sound, text..but also the amount of participating users at that time, users’ age distribution, average time they spent interacting with this artifact etc.

A concept from Team Lab https://www.teamlab.art/concept/Relationships/

-

Assignment 10

Ernst discussed different ways of digitally archiving information and the rise of mathematics in aiding this process. One method he discusses is “on-demand” and while I agree with him that it’s useful for archiving what is most needed first, that may result in the loss of “hidden treasures” or valuable material that isn’t very well known and therefore isn’t “on-demand.” This method may also bias archiving towards the will of those who have most control and not an actual archive or representation of information. I also thought Ernst’s discussion of whether the value of archives lies in the actual information being preserved or the media through which they are preserved was interesting. I think that information is the most valuable currency in this case but some level of preservation of the actual media is also important to preserve the emotions associated with the information

-

Assignment 10 - Digital Memory and the Archive

Wolfgang Ernst discusses and classifies potential means of technological archiving of different types of media, from art to video. Although his writing is quite confusing and could make use of more examples to support his claims, he does bring up some intriguing points that highlight the defining nature of an archive, and delves into key elements such as permanency, power/usefulness, materiality, formatting, etc.

To me, an archive is one that needs to be permanent; the rules of storage and classification are defined and then the content is modeled after those rules. Accessing the Internet as an archive, for example, changes often due to the changing rules for extraction and classification since search engines constantly update their algorithmic criteria; for this reason, the Internet does not encapsulate the identity of an archive (to me). Additionally, to answer the question of the power of archives lying in their security of materiality or storing information, I believe that a great archive does both. One has to be sure of the material authenticity when accessing an archive, and one should easily be able to access that information or else it’s not a very helpful archive.

As a side note - in the beginning of the chapter Underway to the Dual System, Ernst mentions a type of archive that takes shape cumulatively as a shift to a generative, participative form of archival reading; this reminded of the memex due to the focus on contextually shaping the archival narrative.

-

Digital Memory and the Archive by Wolfgang Ernst

Honestly speaking, there are many terminologies in the given excerpts that I’m not at all familiar with, like “media archaeology”,”media art”,”microarchives” etc, there is an absence of context in my mental library which renders the text confusing to me.In this three exerpts, I didn’t see direct description about how classical archivists work with archive(maybe this is discussed in other parts of the book), and this gives me the impression of disregarding the work being done by classically trained archivists in the fields of media preservation and web archiving. Also, Wolfgang heavily focuses on the ontological and epistemological level,which shows a bit indifference toward applied disciplines highly relevant to media and archives and an unwillingness to re-contextualize his media-driven analyses into more human contexts. Yet, I can still get a general idea of the excerpts that the digitization of archive is minimizing the spatial and and temporal scale of the archiving into differential level, making the inherent storage function of archive more and more transient, storage is nothing but a limit value of transfer, the traditional separation between transmission media and storage media becomes obsolete.

Enter text in Markdown. Use the toolbar above, or click the ? button for formatting help.

-

Digital Memory and the Archive

The excerpted parts of Wolfgang Ernst’s book provided a perspective on archive that greatly focused on technology rather than archiving itself. I found his writing rather confusing, and I struggled to see where he was going with his distinctions between storage, transfer, memory components, etc.

That being said, his perspectives on archival science working its way into other “fields” worked a bit better. In some ways, I wish he had compared some of the instantaneous, “current archive,” and past archive ideas in the works of news and newspapers, since they could provide a bit less technical of an example. “Instantaneous archives” and related new-knowledge are becoming some of the most prevalent forms of information in the forms of social media and interactive media. As such, research into their usefulness (and ways to enable those use cases) are important.

Some Notes (as archive!)

I was a tad confused by the pieces, so I tried to compile some of the points here.

Temporality and the Multimedia Archive starting on page 77;

- Ernst started as classicist

- Brings historian tools to discussion of memory and storage in media cultures

- New vocabulary: read-only vs random access, registers, accumulators, buffers, cycle and access times, latency

- Overall different notions of archive

Underway to the Dual System (pages 81-94);

- Digitization on demand as a model–generate new archives according to current needs

- Participative form of archival reading (generate data together through their queries)

- Dynarchive

- Von Neumann architecture: accessing data during computation

- Digital archives as information theory-informed art

- Erasure as a feature (there or not)

- Instantaneous art: does it need archiving (yes)

- Format-Based Archives: images to images. Media vs. Format

- Archiving Software

- Data storage and display are completely separate–can transform in between

- Emulating past materiality with software (old storage methods)

Archives in Transition (pages 95-101)

- Storing “algorithmic dynamics instead of documentary stills”

- Computer memory closely couples storage and timing

- Empathetic cultural memory: oriented towards eternity

- Intermediary media memories: no longer separated into current and archive. Example of soccer match being posted an hour after game

-

Can We Archive the Internet

Fast Changes

I really liked the discussion of the challenge of how to archive a constantly changing beast. Due to the ever expanding size of the internet, it’s really difficult to view it as discrete states. Instead, we have to “approximate” our archives by taking snapshots at discrete intervals. While this seems to be effective, we may miss out on materials, and it is a brand new issue due to the vastly larger amounts of knowledge that we are putting into recordable forms (this is not a problem–it’s what is going to drive humanity forward together).

Legal Issues

The legal issues surrounding international archives prompted some questions from me. Why are international archives different from book archives? And how do governments expect to regulate reading of public information? Also, how could archives be used as an informational weapon (kind of like the Russian interference in the 2016 elections).

Since the internet is really a first stab at a global collection of knowledge, I am surprised a larger governing body like the UN or something of the sort (maritime court is the only other one that comes to mind) has not made a bigger attempt to record changes to this knowledgebase. It appears that private companies have made the best attempts so far, even though long-lasting archives have historically been managed by governments. This also prompts another question: who is best to trust with this important task?

Side Note

This article was particularly funny to me since I’ve known of Brewster in a social setting through my mom’s friend group from when she was a student here.

-

The Web as History

The Web as History_Using Web Archives to Understand the Past and the Present

This article mainly discusses about how web functions in society and the relationship between web archives and researchers. The most impressive part I found in this article is when articulating whether the web is a single entity or a series of clusters. The author mentions China as an example. I would like to further develop this example.

As known, China is using a great fire wall to ring fence the web. I think one reason for doing so is to promote development of domestic product. For instance, China blocked Google and developed Baidu as a substitute of Google. Although Baidu is limited when searching for some politically sensitive words, it still becomes the most popular searching engine in China. Another example is TaoBao.com which is facilitated to be the largest online shopping website as a result of government blocking e-bay. And for reasons of language, the China online consumer market is seen as daunting for many foreign brand owners, which further assists TaoBao to monopolize the online market.

As a result, 90% of ecommerce in China is done in domestic online marketplaces. This might create false impression that “Chinese citizens are primarily interested in content produced in China”, just as Wu and Taneja point out. But personally, I doubt this comment. In TaoBao’s case, government is deliberately building up a new online market culture in a confined local sphere taking advantage of controlling the access to web and possibilities to reach outside.

For most of Chinses citizens, in most cases, they are limited to only domestic online shopping website. Before they realize it, their life is already taken over by overwhelming advertisement of local sites like TaoBao, Tianmao.com, leaving no space for even questioning where to find other choices. The door to outside is blocked and no one even notice that. But I wonder if they were offered multiple choices, would they still choose what they chose before?

-

The Cobweb - Jill Lenore

It was enlightening for me to read about how high the percentage of disappeared content and “link rot” or “reference rot” is, which is surely troubling in legal and scientific spheres. While Perma.cc seems a promising solution, it will take time and effort to reduce and eventually eliminate the problem.

As universal as the Internet Archive seems and is, with its comprehensive collection, generally open access, and relatively high usage, I was quite disappointed to read that it does not completely archive or preserve a webpage, (the 2012 presidential campaign ad example) and that the archive is only recorded and sorted by specific URLs. This makes it highly inaccessible despite its openness which is really a shame, as it undoubtedly houses a vast quantity of information potentially useful.

This issue really highlights the role and importance of digital humanities as a field, to develop tools that enable and improve access and usage of digital material. However, it does seem that this endeavor would require much time and effort, starting with “[seeing] what [scholars] tried to do, and why it didn’t work” for example. The process can also be highly challengin because “it’s a chicken-and-egg problem ‘We don’t know what tools to build, because no research has been done, but the research hasn’t been done because we haven’t built any tools’” Nonetheless, accessing and integrating web archives into research is and likely will remain an area of intrigue and worthwhile venture.

-

The Cobweb - Internet as an Archive

The Cobweb. Can the Internet be archived? by Jill Lepore (New Yorker, 2015)

I thought the story opened up with a very frightening but important example of how the internet can be an archive, but not necessarily in it’s standard ephemeral/easily-editable state. Does this mean we archive the entire internet at all times of the day? The only platform I can think of that archives itself is Twitter, with the Library of Congress archiving every tweet. The interesting thing is that this doesn’t stop people from deleting their tweets. My only other reasoning is that they don’t want to deal with the real-time backlash and people replying to and/or retweeting the tweet, but people can still reply to the tweet’s author and send their commentary without the tweet existing. Throughout Lepore’s discussion of how the internet was formed with ease of use in mind rather than preservation. I wonder what the web would look like had preservation had been an important factor in building the infrastructure of the internet. Perma.cc seems very interesting, and will hopefully be a vital digital humanities tool to solving the problem with rotten links in scholarly documents. I also think the Memento project, in it’s ability to link various archives together, helps solve the problem initially stated with various countries and organizations wary of outside parties archiving their digital footprint. However, I wonder how much biases organizations have when archiving their own data. In general, I’m very glad organizations have taken initiative to archive their websites. During my research earlier this semester into AI fairness and ethics policy recommendations in the US government, I would have struggled greatly if there hadn’t been an archive created of various whitehouse.gov pages specifically from the Obama administration, as they no longer exist on the current whitehouse.gov.

-

The Cobweb Commentary

The idea of an online library of all pages that are on the internet is something that comes up quite often in popular culture, though not in the same terms. It’s something that most people seem to believe already exists; most of the time, conversation centers on the privacy issues that naturally come with such a library. Lack of understanding aside, legal issues are something that definitely will come up with the Archive. As noted, it operates under an opt out policy, unlike the LOC’s opt in style. Additionally, the crawlers don’t seem to take copyright into account, which begets an array of legal questions. Examples like the UK Conservative party’s speech clearing makes these archives sound like they could spur the government to make copyright laws catch up with the internet age. I think that these archives will be subject to a number of legal restrictions that make Kahle’s goal of democratizing access to internet archives seems really idealistic.

One of the more interesting speculations that comes up is how the archives could be used for academic study, both now and in the future. There are a number of roadblocks up now and the current archive is more useful for one-off webpage lookups than any structured work. The sheer amount of information out there has two main effects on the usefulness of the archive. Organizing it would be very difficult and could take multiple forms, each with its own limitations. Simultaneously, there would be very real research benefits from having this many unchanging resources at hand. I’m curious to know how Europeana was organized and how widely used it is.

-

The Cobweb: Can the Internet be archived? By Jill Lepore

This article was really eye-opening. I had always thought that whatever goes online, stays online, and that nothing can be truly deleted. And while that may be true of a hard-drive, Lepore highlighted the importance of internet archives by demonstrating that, information can be removed (the all too familiar “link rot”), or even worse, “overwritten” (content drift) which is arguably more dangerous because one can’t tell if he/she are looking at the original or modified page. I think “Memento” is a really interesting response to content drift, allowing the user to see a webpage at different time points by searching internet archives, such as the Wayback Machine, and adding another dimension to the internet. I was really interested in seeing memento in action so I downloaded the extension and looked at the wikipedia page for “Optogenetics” from 2005 and today. 2005

Today

I was amused, but not surprised, to see that the page had gone from a skimpy one paragraph to a multiparagraph page with many subtopics. Overall, I think memento is a really useful tool and I’m surprised more people don’t use it!

-

Ralph and Niels, The Web as History

According to Ralph and Niels, although web as a new form of media embedding gigantic sources of knowledge and information, it remains almost untapped source for research even in the academic realm, researches on how exactly people are engaged with the web and the information it contains has yet not being fully studied. This book aims to make a start in this direction.

In this introduction part of the book, they started with the argument that the web is not a single entity as is commonly perceived in the English speaking culture, it is a series of clusters influenced by linguistic factors and policies of state and sites promoting shared interest such as commerce and personal relations. They also pointed out that the way people store and manage information with web is different from the way in which they keep diaries, photo albums and other collections of mementos.

On the scholar side, they spilled a lot of ink over introduction of the history of digital archive, which is a good knowledge to know but a little bit tedious. There’s one thing upon which they make a good point is that they call for sustainable collaborations to be created to ensure common standards, as well as better tools for researchers because currently the web archives and researcher communities are developing independently.

The authors also brought about possible future topics based on relation of the researchers and the web. One topic I found very interesting is that the shape of the web is constantly evolving, the form of the web will greatly influence the behavior of people in terms of extracting information from it.

Ralph and Niels intention of writing this book is good, but they didn’t give a clear definition of the archive web, is there an autonomous type of websites that could be called archive web or can I say the entire internet is a huge digital archive web because search engines such as google can help you reach almost every piece of archive in stored online and they are much more sophisticated than any other search tools embedded in those websites specific for digital archive.

Enter text in Markdown. Use the toolbar above, or click the ? button for formatting help.

-

Can the Internet be Archived?

Commentary

This article really spoke to me because I had just been thinking about the issue of link rot last weekend, as I wrote a term paper and added citations. The internet is amazing in that I can read one paper and then, for more details, I can google search any paper it cites and pull up a copy to read (unless there is a paywall). I made notes of the URLs at which I had found each paper I referenced so that, if I were to read my own paper again years in the future, I could bring up all of my sources. However as I did this I became worried - how do I know those links will still point to the same documents that they do now? The internet gives people the impression that they can have access to any information at any time, so we get lazy about properly storing hard copies of things. But this is dangerous, because this impression is just an illusion and pages are constantly being deleted and changed. I thought it was interesting that the article brought up how changing a page can be even worse than deleting it- with no version history, you may have no idea that it had actually changed since you last looked at it. I’m very glad to hear about the internet archiving projects that the article describes, but it seems that these projects have a long way to go in terms of usability and searchability. In this age, most of the world is excited of creating new things, “trying to get it to go” as Tim Berners-Lee says, but especially in the era of “fake news” it is high time more people focused on the issue of preserving knowledge.

-

Can the Internet Be Archived? - Commentary

I personally feel that we always think of “The Internet” as this large, monolithic entity that can’t be recorded or archived in any way, and yet, we always say that once something is on the internet, it can’t be deleted. Of course, those two beliefs clearly contradict one another. The essay’s recurring example of the blog post abou the downing of the airplane is a good example of why we need the archiving capabilites and how they can come in handy. But what if nobody had pressed the “archive button” in time? The blog post would have been lost forever, and so there are clearly large differences between publishing on the web and publishing in print. This essay does a good job of pointing out that the internet can in fact be archived, but never immediately and not all at once, so there are limitations.

I never knew that there was an Internet Archive recording almost everything on the public web, and the idea of doing so seems daunting, especially since there just so much information out there. I was fascinated by Kahle’s claim that the internet would weight 26,000 pounds, as that is a much more reasonable to think about than just the abstract idea of “the internet” or “the cloud.”

-

Assignment 8: The Web as History

The Web as History

##This article mainly discusses the role of the web in society and the dynamics between the web archives and the reasearchers. The extent of the impact of the web is very large and on global level. The examples in the text, including China,the 2014 shooting down of a passenger plane over the Ukraine during the war between Russians and Ukrainians,and UK Conservative Party reminds me of the phenomenon fake news during the last U.S. presidential election. I would argue that the web plays an important role in the spread and virality of fake news. The ability to share information globally on the web shifts the dynamics of information and readers. Not only you get the source of the information, now you know who share that information. The significance of the news can change dramatically if an important figure shares such a news globally.

Further, the web gives off this aura of a place of freedom of expression and a open source of information that is under the people’s control. We often don’t see the context of the web and its behind the scene. To a great extent,it is a platform of free expression and a great source of information. However, it is greatly influenced by the people at the top. For instance, facebook and twitter were suspected of blocking certain information about the presidential candidates during their campaign in order to endorse one over another. The worst part was that they are so powerful that they could discreetly narrate the stories as if they were the definite truth or the reality.

It is incredibly important to understand the context, culture and the history of the web in order to understand its biases. It also helps clarifying any confusion that the web is some alternative reality that holds the truth.

-

Archiving the Internet

“A lot of people do believe that if it’s on the Web it will stay on the Web” is a highly accurate statement that does not match how ephemeral the existence of content on the internet really is.

One of my friends google-searched an obituary of a favorite writer of hers for a research paper, and when she clicked the link that was supposed to take her to the piece, she was redirected to a web page about a big win for a random baseball team. This is an example of the “content drift” that the New Yorker piece talks about, and the only way to find the original web page was to call up the journalist who’s name was next to the article’s link; he ended up emailing her a PDF of the article. This entire process felt extremely outdated and cumbersome compared to the expected speed at which my friend thought she would be able to access a simple journal article on the web.

The issue of not being able to access the obituary of a writer feels like a nonissue this it’s such a specific uses case, but what if all of of the files we uploaded to google drive or dropbox disappear?

The solution of archiving the internet seems like a no-brainer, but it also seems impossible to compile and index every single piece of content on the internet. In 2013, “Google performed 2 million searches each minute and 72 hours worth of video was uploaded to YouTube within the space of 60 seconds.” And, in 2012, over 140,000 websites were created each day, which has probably increased dramatically since then. There is a vast amount of existing content before even figuring out which content is valuable enough to archive. Then, there’s the question of indexing relevant content.

-

The Cobweb

The Cobweb. Can the Internet be archived? by Jill Lepore (New Yorker, 2015)

Digital archiving and saving webpages from the internet is becoming increasingly important as the internet becomes increasingly important and intertwined in everyday life.

The most surprising thing that I found while reading Lepore’s article, was the lack of proper redundancy in internet archiving. While I had known about the Wayback Machine for a long time, I didn’t necessarily realize that that was the only archival tool for the internet–I also did not put together the importance of it being an “opt-out” service.

Sites like Perma.cc seem to be very important for academic and scholarly reasons, for the same reason that the Memex is important. However, it is an opt-in service. While that serves a good enough purpose, it mostly serves “ as the standard in legal, scientific, and scholarly citation.” As the example in Lepore’s article illustrates, sometimes it is necessary to have an opt-out service because it captures all of the going-ons in the internet.

I think the article frames mostly one advantage of having the Wayback Machine that is more related to the idea of catching the bad guy–with the record of the Russian social media site, the value of archiving the internet is easy to understand.

However, internet privacy and lack of record is something that is important as well. The Minitel is an example of a pre-internet system that was inherently private. When changes were made that compromised this privacy, there was immediate backlash.

-

Text as Data "Mini Project" Commentary

JSTOR TopicGraph

Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers - JSTOR TopicGraph

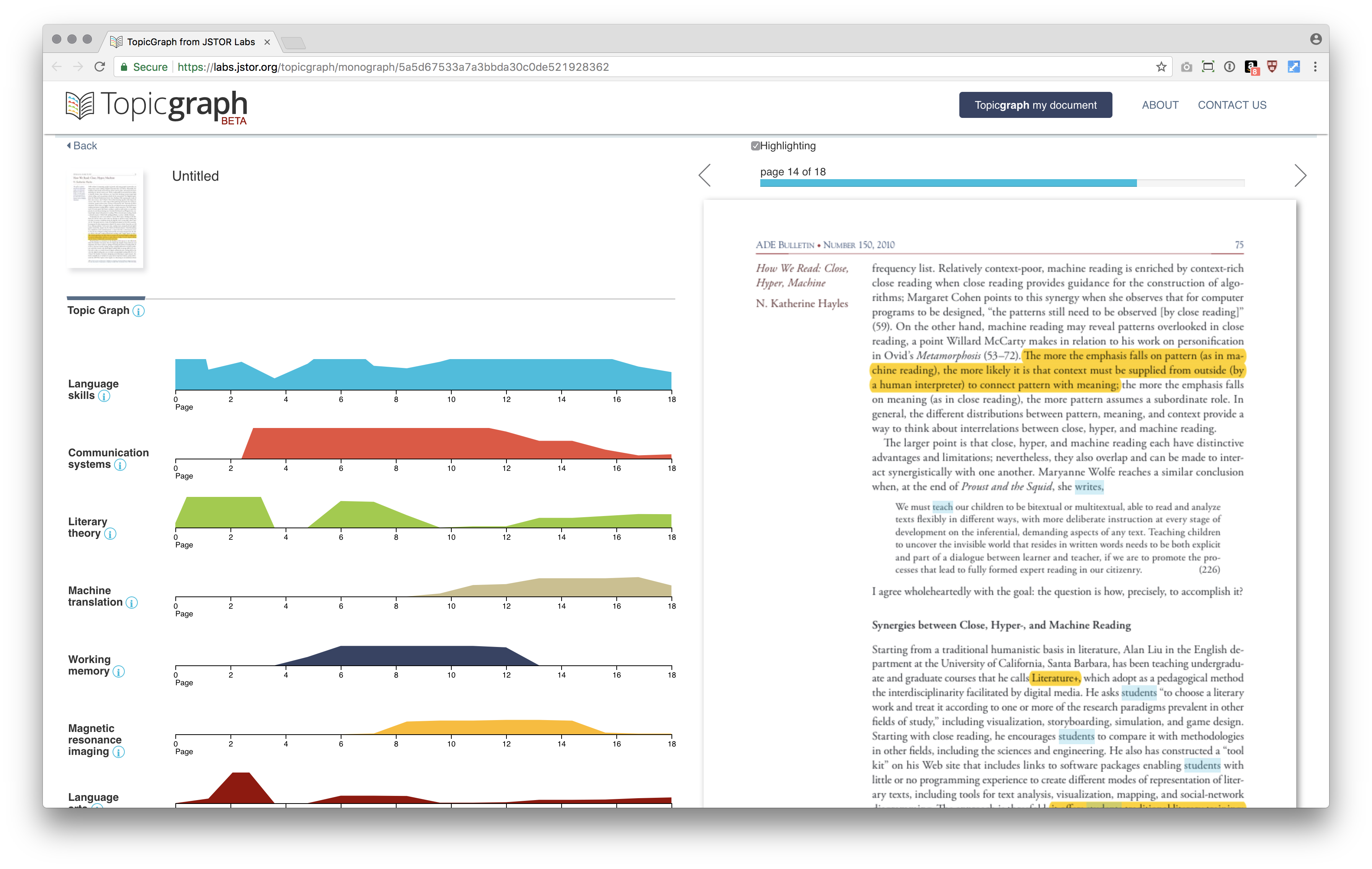

Our group tried out JSTOR Labs’ “TopicGraph” Beta Version, which aims to help you “understand at a glance the topics covered in a book, then jump straight to pages about topics you’re researching.”

TopicGraph either provides a range of books from a multitude of academic disciplines for users to choose from, or allows users to upload a PDF of a document already in their possession. We uploaded a book by Stanley Cohen written in the 1960s, titled “Folk Devils and Moral Panics: The Creation of the Mods and Rockers.” For context, this book seeks to explain the vilifying stereotyping of certain groups of people. It highlights the phenomena of moral panics and how the media creates scapegoats out of these people, the folk devils, to shift the blame on them for crimes and social upheavals.

This is a helpful resource to understand the overarching topics within a book or paper at a glance, and allows users to actually dive into the pages of the book itself. The interface is easy to visually digest and navigate, and the extracted information accurately portrays the themes and vocabulary of the text we imported. That being said, this would be a great “first look” when deciding whether a source might be valuable in the scope of one’s research, getting a brief synopsis before reading the entire source, and even finding a quote that uses a specific and relevant term, but it in no way is a substitute for reading the actual material. It merely extracts information; it does not infer anything or make assumptions, but rather conveys the general “identity” of whatever source you uploaded. It would be interesting for JSTOR to take this tool further with machine learning/linguistics analysis by potentially attempting to interpret the tone of the writing, the arguments the author is making, and even the historical context behind the writing and publication of the source. These kinds of interpretations would elevate this tool from one that naively extracts information to a helpful tool that helps users understand the complexity and nature of the text they are attempting to learn about.

-

Assignment 8 Commentaries and Mini-Project

Alien Reading: Text Mining, Language Standardization, and the Humanities

This article takes a proceed with caution approach to using text mining software in the humanities. It points out that these softwares are a best fit model that was trained to scientific and news focused texts and fails on humanistic test data. Binder notes that many ignore the fact that these text mining tools can’t be separated from the circumstances of their creation when they are applied to non-standardized works. For example, when a software looks for topics and associates texts with topics, it ignores nuances associated with creative writing. These bag-of-words type assumptions, which ignore syntax, ignore the human aspect of writing and limit interpretability of humanities texts that prioritize aesthetics over pure information. I thought the conversation about how these models need to avoid overfitting but have accurate results was interesting given that there isn’t any ideal way to interpret certain works. Clearly the critical approach described is necessary, but I wonder if there are any other types of statistical method that would work other than this (seemingly) tree based model.

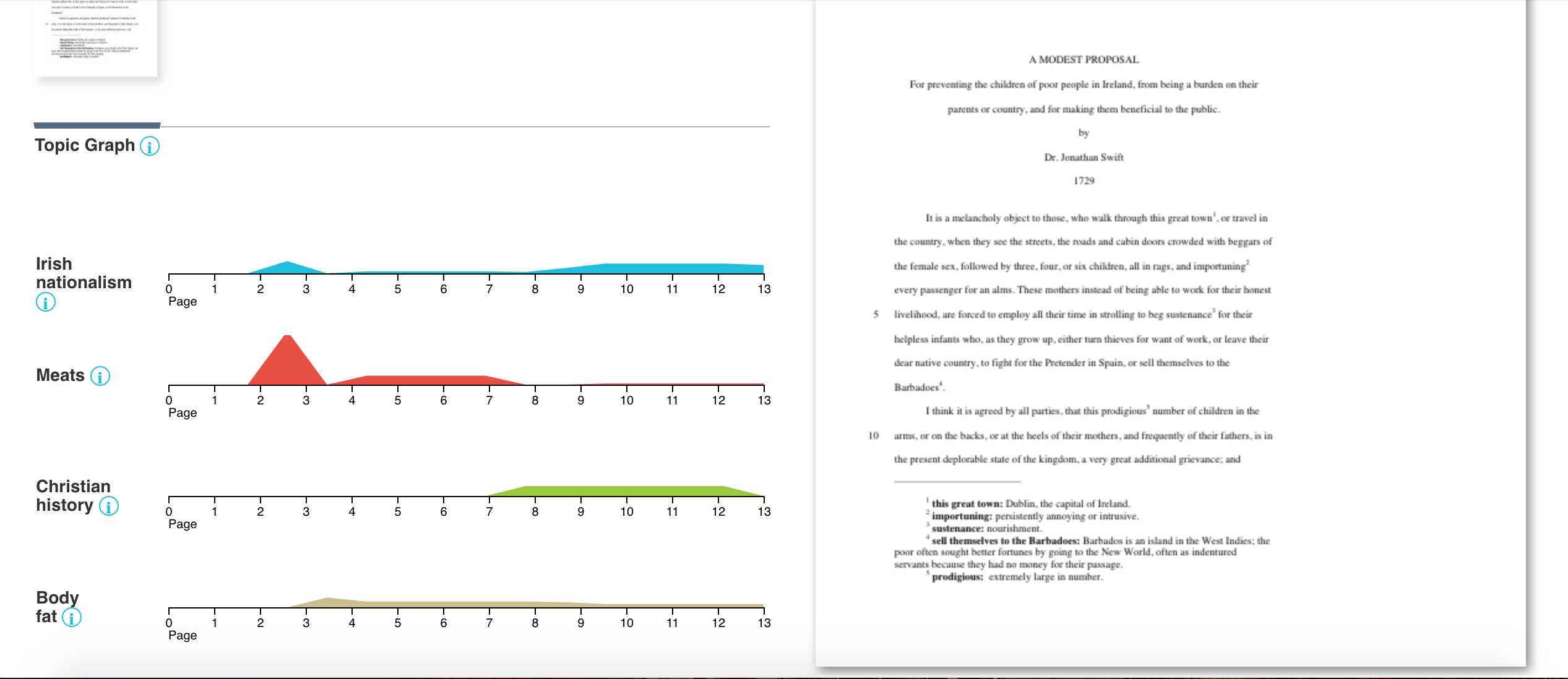

Text as Data: A Modest Proposal, JSTOR TopicGraph

I tried out the TopicGraph for the mini project and decided to analyze A Modest Proposal by Jonathan Swift because I was interested in how the tool would work with a piece of satire, especially given its goals of enabling you to quickly understand the topics covering in texts

The tool is straightforward, allowing users to either choose from a selection of documents or upload a pdf version of their own. After uploading, it pretty quickly sends an email notifying you that the document is ready. You’re linked to an easy to read and well-structured website which lists phrases that occurred most frequently. It also allows you to go to individual pages, which I found particularly useful.

Some of the words/word strings it picked up were “Irish Nationalism” “Meats” “Christian History” and “Body Fat” which are definitely relevant but on their own don’t contribute much to understanding the text itself.

Ultimately, this tool isn’t one that can be used for a deep and involved analysis of a text, since it misses important contextual clues and priorities word count instead. That being said, it is a nice way to get a vague idea of what is going on in the text, and how the author is trying to get their point across.

-

Mini project-text mining

We explored both JSTOR TopicGraph and Voyant and compared their functionality below. Our testing article is The Public Sphere: An Encyclopedia Article by Jurgen Habermas. Before using those tools, we were expecting to extract the keywords or most frequently occuring words that imply overview of the article, and to understand network and logic among the extracted words.Both tools are pretty straightforward to use, but they display different features.

JSTOR TopicGraph allows us to compare the extracting information and articles horizontally. It extracts “topics” automatically and shows what topic are covered in this book. When clicking on graphic next to topic words, users are led directly to a page that discuss this topic. However, Topicgraph doesn’t display how the topics and their related terms are chosen. Users are not allowed to edit topics and related terms. The relationship and network among different topics are not analyzed either. http://voyant-tools.org/?corpus=eb5e4b4483871aa09c310d81c5bd51e1

VOYANT has more features in terms of analysing and visualizing the data. Besides the basic visualization of text frequency, there’s bubble diagram showing the relations among the key words; Filters are also provided for more accurate analysis;The number of text segment can also be customized, all these additional features provides more information and flexibility for the user to understand the text, making it more powerful than JSTOR in terms of data interpretation. https://labs.jstor.org/topicgraph/monograph/324348d0eab2692439be05e7217dae29

-

Assignment8

Alien Reading: Text Mining, Language Standardization, and the Humanities

In this article, Binder introduced LDA,a useful tool applying text mining technology for topic finding and stated the fact that LDA performed perticularly better when it was fed with scientific texts. The possible reason for this phenomenon, according to Binder is that the vocabularies of scientific texts correlate with their topics in a more uniform fashion than that of a poem or a prose, which accords with his argument that “there’s a congruity between text mining and the language standardization efforts”, both of these methods “tend to reinforce the ‘literal’ conceptions of language and meaning” and marginalize the “nonstandard linguistic conventions and modes of expression”. He further analysed the statistic nature of the tool that output only meanings with largest probabilities and ignored other meanings that valuable but with smaller probabilities. This marks the inherent limitation of topic modeling tool and other statistic analysis based tools in dealing with the existence of “non-literal” language which consists a significent part of a certain humanistic database.”If we are to adopt text-mining tools in humanistic research, we will need to take account of the assumptions they make about language and how those assumptions could serve ideological interests”.

It is interesting that Binder associated the newly emerged text mining technology with the language standardization effort dated back several centuries ago. This historical insight has profoundly demonstrated the efforts people are making to tackle information abstraction from large pools of database.The technology of text mining is still in its early year, despite the limitation, it works well in analysing and associating numerous amount of literature or achive, where the overall trend and feature of the database comes more important than details.

Enter text in Markdown. Use the toolbar above, or click the ? button for formatting help.

-

Assignment 8

Alien Reading: Text Mining, Language Standardization, and the Humanities

Enter text in Markdown. Use the toolbar above, or click the ? button for formatting help.

It’s clear that the current text-mining technologies is still limited and cannot read text the way humans do. The argument in the article is that there is little interaction between the scholars who apply these computational methods to literary history and those in media studies who critically analyze the history and culture from which this technology emerged. For instance, scholars who use text mining in literary and cultural history often do not consider the question of how the technologies they use might be influenced by the military and commercial contexts (from which they emerged). As mentioned in the article, a dialogue between media studies and text-mining should exist to allow scholars to engage with the linguistic technologies in a way that keeps their alienness in sight, foregrounding their biases, and focusing on the historical and cultural context of how computers read text.

If we critically examine the texts in which these methods are applied, we see that the kinds of text that these technologies parse share certain characteristics. They are primarily written in a standard dialect and orthography; they tend to privilege the informational over the aesthetic dimensions of language; and they primarily consist of prose. This is a very interesting point since these texts are not randomly selected to be read by parser. The technologies were designed for these specific kinds of texts. Some of these texts are the sorts of text that the military-industrial apparatus would have a clear interest in mining. In fact, the military was partially responsible for the birth of these technologies. Users of the text-mining technologies and even the general public are unlikely to know that fact. It’s scary to learn about all these powers behind the technologies that ultimately shift the entire society. It is more frightening that they are directly and indirectly influencing our lives and our children’s in various aspects without our awareness.

In addition to our experimentation with text-mining methods, we should also focus on research that situates them historically—both in the short term, looking at the institutional contexts from which they emerged, and in the long term, looking at how they relate to the histories of linguistic thought, philosophy, communication, and labor organization. I strongly think it is important that there is some openness about the behind-the-scene of these technologies. There should be someone to critically examine in the context and the drive behind these technologies and not just their applications and direct impact. Further, focusing on the research of the historical and cultural context of these technologies keep them in check (in term of biases) and help general public better understand them.

-

Assignment 8 Reading & Project

Binder - “Alien Reading: Text Mining, Language Standardization, and the Humanities”

I thought this reading was a very necessary examination of the text mining and other analyses being done on large quantities of text, and the implications that can arise by relying on them alone for analyses previously done by humans and their very human paradigms and language comprehension skills. One of the various approaches I thought was very interesting was when Lisa Marie Rhody uses LDA to produce topic models for poetry, she can’t use the resulting models in the same way that someone using LDA for more scientific documents might. However, that isn’t to say that the information is not useful. Rather than accurately determining what the poems are about, the topic model reveals how the poem is structured and possible traditions emerge. I thought this was very cool, and a good nod to the idea of using these models to “suggest” or “reveal” something about the text, rather than providing absolute analysis. I think this mindset is one to hold when using various computational text analysis methods. While continuing to read on, I wonder if there are text analysis methods that more successfully understand more complex forms of language, such as poetry and fiction. As I read on, I realized that Bogost agrees with me, as the text states “this approach would involve encountering text mining as an alien form of reading—alien both in the fact that it emerged from a discipline with very different concerns from our own and the fact that it is performed by a machine, the sort of nonhuman agent that Ian Bogost has sought to understand with his idea of alien phenomenology”. I also was pulled into Sturm and Turner’s idea of thinking of “computation as a ‘a caricature of thinking’”, and would definitely want to apply that ideology to other computational methods, like neural nets. But as this article concludes, we can’t use these caricatures for real understanding unless we also situate them with human research and analysis that looks at historical backgrounds of the text as well.

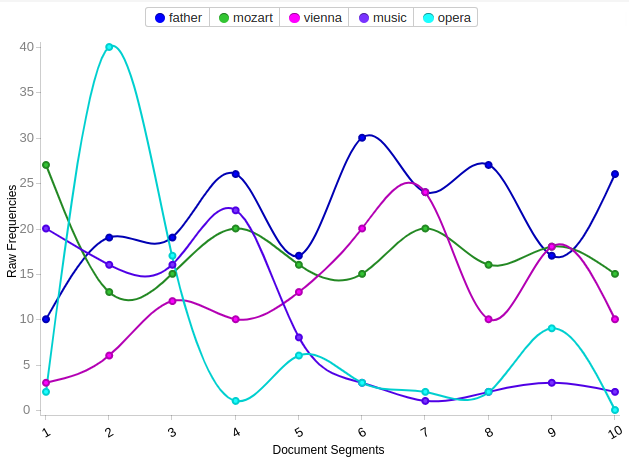

Mini Project: Text Mining & NLP

For this mini project, I decided to use Voyant to analyze the text I chose, mostly because it seemed more complex than the other tool I was exploring, Topic Graph. The text I chose to analyze was Mozart: The Man and the Artist, as Revealed in his own Words, by Friedrich Kerst (translated by Henry Edward Krehbiel), obtained off of Project Gutenberg. When I was pulling the document from the site, I was wondering if I should remove the project gutenberg text before the actual book text, but decided against it. After doing my initial analysis however, I decided to go and remove the project gutenberg text, as well as the urls that would continue to appear throughout the rest of the document. This turned out to be a smart move, as it gave me much more accurate results. Voyant revealed that the document had 32,688 total words and 4,714 unique word forms. It also revealed that the most frequently used words in the corpus were “father, mozart, vienna, music, and opera”. This makes sense, and also displayed in the word cloud that Voyant generates. I think this definitely gives a basic understanding of what the text is about, which is Mozart, his life, and his music. However, I think this information could have just as easily been understood from just reading the title. I guess the frequent words list reveals more that Mozart is specifically a musician who lived in Vienna. It also revealed that Mozart talks a lot about his father, which was unexpected. The trends graph was also very revealing, as it showed various trends of the main themes throughout the document. For example, the obvious trend of mozart stayed rather consistent throughout the entire document, but opera is heavily discussed in the first third of the book. His discussion of vienna and his father continuously dip and rise in an upward motion through the novel. Because this is a musical-themed text, I think it would be very interesting to develop a specific machine learning technique for scraping the musical themes and definitions Mozart uses, and extract his “musical intuition” and inspirations from the text. This technique could be translated to other musical texts as well.

-

Assignment 8 - "How We Read" Commentary

My first impression of this reading was that it cast a pretty ominous cloud on predicting the future of reading and critical interpretation. Seemingly, people are becoming lazy readers, and the argument is that technology is affecting the reading abilities of younger generations. This criticism is one I face in my academic/professional life – people want to see a design portfolio with more images and less text; obviously, it’s important to be able to story tell visually, but can images ever fully convey what we wish to communicate without the aid of words? Furthermore, when it comes to designing for mobile interfaces, designers understand that users do not read text. It’s a tough situation when a mobile app screen with both image and text ends up being too much text for young users (who ignore the text), and not enough text for older users (who wish there was more).

Yet, there are always criticisms when things change from the norm. Just because people are reading differently in a different age doesn’t mean it’s necessarily a downhill path for reading – reading can be taught in a way to account for the rise of technology and increase in new media and methods for digital reading. For example, I’ve been in classrooms where students were taught to read the page of a book line-by-line using their index finger to point as to not lose their place in the page. This technique was pretty specific to print reading, but new kinds of techniques can be created and taught in terms of digital reading; the rise of digital reading doesn’t have to mean the end to close reading. Maybe tools like a more robust version of the TopicGraph tool can help to augment digital reading environments with keyword searching, or can even can aid users in learning and understanding something through key word indexation. All hope is not necessarily lost :)

-

Alien Reading

Alien Reading:

In Jeffrey Binder’s text, Alien Reading: Text Mining, Language Standardization, and the Humanities, I found that Binder brings up a lot of points that I have been interested in regarding technology, algorithms, and their relation to cultural, social, and political contexts.

A key quote that I want to respond to in Binder’s essay is: “If, as scholars, we are to engage with these technologies on our own terms, then we will have to find a way of making their roles in humanistic research a matter of active concern. Experimenting with text-mining programs in English departments could serve as a safeguard against the possibility that we unknowingly absorb these tools into our practice without reflecting on the assumptions about language and knowledge that underlie them and considering the effects they could have on our work.”

Two notable example that relate to this idea of standardizing language and text mining come to mind: Facebook “Trending” algorithms and the Microsoft “teen Twitter bot.” Both participate in this kind of keyword-association-response, but have created problematic readings of text. With the Microsoft bot, it had to be taken down because the text and data that it was being trained on, rapidly too a turn for the worst and started spewing anti-Semitic tweets. While this is a more extreme example, in that the data was ripe for being corrupted, the Facebook algorithms also contributed to this idea that algorithms had the “last word” and did not require this humanistic safeguarding.

A final note that was interesting to me was the investigation of poetic language and figurative, and how text mining and standardization make it difficult for literary scholars to be a part of the same conversation that highly technical writers can engage in regarding computerized text. The generation of phrases like “dat master slave negro massa slaves white black dis dey” from MALLET is concerning because it does seem to erase, or even render nonsensical, non-white and non-“standard” (whatever that term may mean) language.

-

Alien Reading: Text Mining, Language Standardization, and the Humanities

I’ve been really interested in Natural Language Processing since high school so I’m familiar with many of it’s really cool applications in a really general sense(https://medium.com/@ianminoso/a-textual-analysis-of-harry-potter-by-an-amateur-data-analyst-6f02c09617e0). But reading this article was my first “formal” introduction to the subject and the technical terms associated with it. I agree with Binder that Topic Modeling (for example with MALLET) may not actually give an accurate representation of what a text is discussing, but I do think it’s useful for getting a very general sense of what a text is discussing. However, with poetry and other texts that depend on metaphor, the so called “bag of words” approach, which doesn’t even account for the relative position of words, let alone their syntax, may do the text a huge disservice. Moreover, it’s important to keep in mind that the nature of English grammar is such that improper syntax interpretation (or the lack thereof) can result in a meaning opposite to the intended one even when a text doesn’t contain metaphors. For example, the difference in meaning between “let’s eat, grampa” and “let’s eat grampa” is in a sense, a matter of life or death, but the only difference between the two sentences is the crucial placement of a comma. I think this emphasizes the importance of accounting for syntax and semantics in natural language processing algorithms, a project which many labs here at MIT (especially in the course 9 cognition labs) are working on.

-

Alien Reading Commentary

Alien Reading: Text Mining, Language Standardization, and the Humanities

Text Mining Mindfulness

Much of the field of natural language processing is focused on taking the “natural” representation of information and converting it into structured data, which computer scientists are more comfortable working with. Two summers ago, I worked at a social robotics startup called Jibo and spent a good portion of my summer working on an open-ended conversation handler based on work done with IBM Watson.

In order to do this, we ran a classic approach of using natural language understanding (NLU) to get structured data, used a dialog manager to build a structured output, and then used a natural language generator (NLG) to randomly convert the structured data into more natural sounding sentences. While this abstraction works really well for computer scientists (the intermediate structured step allows for easy storage and a model of the brain that we can understand), it definitely does not pass the Turing test (it is easy to tell that you aren’t having a conversation with a real human).

In this sense, I agree with Binder’s analysis that our current models of language do not address certain human-qualities of language, and I think that this is not a fundamental shortcoming of “topic modeling” or other approaches that will not be fixed in the future. We are still in the “early adopter” phase of widespread NLP, just like how lots of people doubted that people could communicate effectively without being face-to-face before technologies began enabling it the “right” way.

Alien Reading Approach

I only have one quick point here about the approach Binder suggests. Essentially, he just wants to make sure we approach these newly-enabled humanistic problems in a multidisciplinary fashion, and I just wanted to say that we want to make sure to preserve the processes that we’ve used for technology-free learning. We culturally forget how people “used to do things” rather quickly, and we just need to make sure to preserve it. This is just in case we are losing some quality of analysis that we won’t notice is missing in the short-term, but could be useful farther down the road. Analogy: People who forget to ride a bike when they learn how to drive, since they don’t see any benefits to biking short-term.

-

Reading Response Assignment 8

Commentary on Jeffrey M. Binder, “Alien Reading: Text Mining, Language Standardization, and the Humanities”

This article explained how text mining was transforming the humanities, but warns that the algorithms and statistical methods used for text mining behave very differently from humans. We should be careful about how they are designed and what aspects of the text they are capturing because it could reflect false or skewing assumptions. I can see a danger in people applying technical tools without understanding how they work and then drawing incorrect conclusions. I’m really curious about how the language processing algorithms work, given that I have taken a number of machine learning and statistical inference classes. Unlike many problems in machine learning, it does not appear that this problem can just be solved with a large enough quanitity of data. Longer texts could have more complex meanings, weaving together multiple different narratives, and it is difficult to establish “ground truths” to evaluate exactly how well a computational approach “understands” the text.

-

Assignment 8

Alien Reading Commentary

As someone who has had a decent amount of experience in natural language processing (I took 6.864 last year), I found the article pretty interesting overall, but there were some points that could have been improved upon. Particuarly, I agree with his argument that its important to separate the computer’s understanding of natural language with our own; however, there has been extensive progress in computer representation of language in recent years, especially with deep neural models. The author misrepresented a computer’s ability to produce a coherent sentence by choosing to include a piece generated from a Markov chain model, an algorithm which is nearly 30 years old, rather than including text generated from a more recent breakthrough.

While these tools aren’t perfect for studying humanities as they currently are (nor will they ever be), we may still use them as long as we make sure to note that as powerful as they are, they are also limited in many ways.

Working With Stanford NER

I chose to work with the Stanford NER by interfacing with it using Python nltk. It was overall pretty easy to get it working, it just required installing Python nltk and downloading the appropriated JAR files for the Stanford NER. I have reproduced the script below.

from nltk.tag.stanford import StanfordNERTagger CLASSIFIER = `classifiers/english.all.3class.distsim.crf.ser.gz` JAR_FILE = `stanford-ner.jar` def extract_ner(filename): st = StanfordNERTagger(CLASSIFIER, JAR_FILE) file_text = `` with open(filename) as f: for line in f: file_text += line return st.tag(file_text.split()) if __name__ == `__main__`: ner = extract_ner(`ulysses.txt`) print(ner) for word, tag in ner: if tag != `O`: print(word, tag)I tried the Stanford NER on a few poems (“Ulysses” by Tennyson, “Because I Could Not Stop for Death” by Dickenson) but the algorithm unfortunately could not find any named entities. When I tried it on Frederick Douglass’ essay “John Brown,” it performed much better, suggesting that the Stanford NER is unable to perform well on poetry, but excels at understanding prose.

-

Reading Responses

Katherine Hayles, “How We Read: Close, Hyper, Machine”

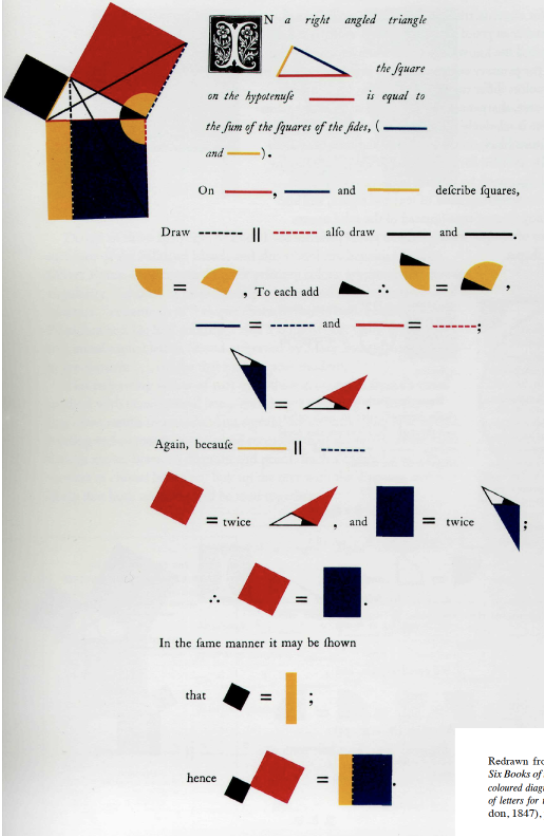

I agreed with all of Hayle’s points, but think she missed one key element of reading on a digital platform: the strategy of layout. For example, reading a text is easier to retain because the reader can recall the page section, location of the spread (L or R page), and their location in the book based on the fore-edge. That said, I appreciated all of the technical references she included to talk about the analogy between hyperattention : hyperreading :: deep attention : close reading. Describing hyperreading as multilocal context but context poor led to this notion, “The more the emphasis falls on pattern (as in machine reading), the more likely it is that context must be supplied from outside (by a human interpreter) to connect pattern with meaning” which provides a good platform for art and scholarly practice.

Jeffrey M. Binder, “Alien Reading: Text Mining, Language Standardization, and the Humanities”

I also really enjoyed this essay, through its technical trail of topic modeling –> latent semantic indexing (LSI) –> latent dirichlet allocation (LDA). Binder ends the essay with a call to action for how to engage with these simplistic interfaces with active engagement, questioning how it is used. He also includes several computational text-based artworks. I particularly liked the reference to deformance (modified versions of text to explore their autopoietic capabilities) and digital caricatures (thinking of computation as a caricature of thinking).

Text as Data Mini-Project

At a glance, it is quite simple to use JSTOR Lab’s TopicGraph to analyze Katherine Hayles’s “How We Read” t. By uploading the PDF, it took about 5 minutes to receive an email that the document was ready. The key phrases and topics are listed in order of frequency. According to this tool, Language Skills was the most relevant topic, used throughout the essay, while Machinery was the least. As you hover over the scales, you see the page number. Clicking leads to that section of the PDF, where you can see the terms (color-coded according to topic) highlighted in the text. This was very useful because you can begin to decipher which terms cause the NLP to assign the various topics. However, I wish this hover would include more context about the term (maybe a pull quote? Frequency of use?) rather than just revealing the page number. You can also click on the information icon next to each topic to see related terms, but this seemed as adequate as a thesaurus, rather than showing true relationships between other ideaologies. Overall, TopicGraph is very easy to use, intuitive and visually pleasing UI, and good at determining key ideas from the text.

-

Assignment 8

Alien Reading: Text Mining, Language Standardization, and the Humanities

In this article, the author tries to point out the gap between human and machine reading, and let us know the complexity debate between the accuracy of text mining tools and the fact that scholars already depend on generative models and other text-mining techniques. The whole argument is reasonable and logical. First of all, the author illustrates the process of machine reading method which is different from human reading and acknowledged that the significance and necessity of text-mining under such big data background. And then he differentiated the characteristics of science articles and poetry which shows the text-mining is more suitable for science articles. Then he suggested that goes further into a critique of the technology itself, engaging with text-mining tools as embodied, historically situated cultural productions that are potentially problematic. In order to minimize this problem, he argued that “supplement our experimentation with text-mining methods with research that situates them historically—both in the short term, looking at the institutional contexts from which they emerged, and in the long term, looking at how they relate to the histories of linguistic thought, philosophy, communication, and labor organization.”

The last part argument reminds me of the articles we read in several weeks ago. The content is that the time and space mapping has been over-simplified in GIS tool and some scholars have adopted this tool for their research for a longtime. It’s important to be wary of the limitation of our techniques and use critical perspective to adjust the expectation and result. Even though we are worried about the growing influence of these imperfect techniques in the twenty-first century, we should admit that the only way to improve this problem is to combine human thinking and machine learning rather than give up easily.

The “non-figurative” poetry debate part also let me think about our project as pop music automation. Just as Sarah mentioned before the lyrics generated from python is not so appealing and beautiful, that could be the difference between our human reading and machine reading.

How We Read: Close, Hyper, Machine

In the first part, the author illustrates the definition of close reading and points out the fact of close reading declining is just a result of trend transformation which isn’t equal to reading crisis. Also, the most important thing here is that the literature teaching should combine digital and print method together rather than separate them. The author argued that teaching should take place in the zone of proximal development and disciplinary shift to a broader sense of reading strategies and their interrelation should be addressed.

Then she explained the concept of hyperreadng which stimulates a new concern about media-induced state of distraction. And she also gave the answer to the distraction question that it lies in the relation of working memory to long-term memory. The small distractions involved with hypertext and Web reading increase the cognitive load on working memory and thereby reduce the amount of new material it can hold. She also used several recent experiments to show that the web reading gives pressure to brain.

Instead of using scientific analysis, the author believes that anecdotal evidence is more useful to understand the situation. She explored the interrelations between the components of an expanded repertoire of reading strategies that includes close, hyper, and machine reading, and found the overlaps between them are as revealing as the differences: Hyperreading overlaps with machine reading in identifying patterns. Then she realized that “close, hyper, and machine reading each have distinctive advantages and limitations; nevertheless, they also overlap and can be made to interact synergistically with one another.” Then she used several examples to show how to accomplish them.

The immediate case came into my mind is the way our digital humanities class organized. In each week’s assignment, we would read two or three articles and connect the concepts with practicing a small project. The assignment not only requires us to read the new concepts and interact with digital tools, but also allows us to think about how to tell a story in digital format and how to improve the experience. This case is very similar to the first example Literature+.

-

Kreps + Macalik Reading Commentaries

The two articles discuss how museums have changed in purpose and approach over time. However, the first article believes that curators should take a didactic approach when creating exhibits, whereas the other supports the idea of a museum as a space that encourages discussion. Although both acknowledge that museums have to adapt to changing social norms, these differing opinions mean that they interpret the role of the curator very differently.

One thing that the first article mentioned that I thought was very interesting was how artifacts come to be in museums; who deems them valuable enough? The arbitrariness of this and the principle of fixed relation is something that feeds into the concepts discussed in the second article. Both articles agree that objects have taken a backseat, but differ on who they believe is the one interpreting the object, and how clearly defined those interpretations are.

Generally speaking, I think that the type of museum influences what type of curation goes on inside, with art/history museums at one end and science museums at the other. This is not always the case, but is true to an extent, partly due museums being slow to consider diverse perspectives on the material being shown. Boston’s MFA and the V&A are examples of museum that focuses on teaching to a uniform and non-argumentative group of people. On the other hand, the DOX is thought provoking contemporary art museum whose purpose is to use are to challenge conventional perspectives. Science and Natural History Museums are interesting because they strike a balance between the two. They have blockbuster type exhibits like IMAX and self-directed teaching, yet are highly educations

-

Digital Curation 1

Digital Curation Site

Enter text in Markdown. Use the toolbar above, or click the ? button for formatting help.

http://cmsdigitalcuration.omeka.net/

We focused on the women of Mairas during this period of time by selecting photos that portray Mairas women. Through these photos, we only get snapshots of their lives and attempt to piece them the puzzle pieces together to understand the whole picture of their stories. We see their daily activities, their status, and their roles in the society. We get a sense that these women’s identities were tied/limited to home and family. We had to manually upload the images and titles so we weren’t able to link the dates, but it was really interesting to see the progressions of the portraits from groups of women to a single portraits, signifying to progression to valuing the individuality of women.

-

Curatorship

Curatorship as Social Practice

This article relates a lot to my work in human-machine interface because the psychology behind it is very similar to the “social” interactions described here. While objects in museums can only communicate outward to visitors, curators and computers alike can have two-way dialogue with repeat visitors and users via their exhibitions and interactions, respectively.

Continuing with the analogy, I agree with Kreps that curation does not have to be object- or people-focused. However, this new lens seems to be communication-focused in my mind. This being said, curatorship is much harder to usability test, and my engineering mindset would definitely frustrate me if I were a curator. While multi-disciplinary skills are common to both fields, they (obviously) differ in practice because quantifying an exhibit’s success is much harder. As I brought up last class, many museums lack concise mission statements because their role in society isn’t completely understood yet. While this makes mission-driven exhibits like storefronts and advertisements much clearer, they intend to affect all people the same (driving them towards consuming a particular good). Museum curators, on the other hand, don’t really want to over-design their exhibits for fear of polarizing discourse towards particular ideas.

The Museum as Discursive Space

Discursive space has become an extremely important topic over the past year due to social media’s newfound importance in our lives (especially our views). As museum attendance decreases, people flock to online exhibits like their Facebook News Feed, Snapchat Stories, or other “user-created” and “user-curated” social media sites.

While these exhibits are (often moreso) engaging than their museum counterparts due to their targeted nature, they more recently have attempted to minimize the polarized, politicized, discussion-fraught, and contradictory-view-surfacing qualities that these editors say are fundamental to curation. Why would they do this? Because their mission for the past few years has been to engage users as much as possible.

I particularly enjoyed this article’s discussion of this issue because it finds a happy medium between engagement and connecting (not connected) content. While museums can cater to the modern westerner’s lack of patience for one-way communication, they can also avoid the community-polarizing nature of social media that does not connect diverse visitors/users with contradictory views and opinions. The real question is, how much effort will it take to save us from our own opinions and those that match?

-

Curatorship Readings

Museum as Discursive Space

I found it particularly interesting how this article brought up power roles that are present in museum spaces between the “guests” and the “hosts,” which is not something that I’ve ever thought about. I think the traditional museum setup definitely has these power dynamics, where the hosts certainly are inviting visitors to see their collection and take away a specific message. That being said, I haven’t been to any museums that allow the user to “engage in a dialogue” as the article states. Most musuem experiences that I’ve had are pretty one-sided, though I could see how some museums of science fit into this description, as they tend to be much more engaging through their use of interaction rather than just showing.

-

Curatorship as Social Practice and The Museum as Discursive Space

I very much agree with Kreps’ proposal that curation is a form of social practice. I could really relate to the idea because I went to on a trip to the MFA for a class last fall on Islamic Archiceture and it was lead by the curator of the exhibit. At the time, I thought it was weird that the curator was guiding us through and explaining why she chose to display the pieces she did, but having read these two articles, it makes sense in reterospect. I also thought it was interesting that “curator” is derived from a latin word meaning “to take care of” and that using this definition, the term curator can be expanded to include other individuals such as spiritual leaders. In fact, I think it would be interesting to think of teachers as curators of knowledge, not just as creators of educational programs as Kreps described them because a very important aspect of teaching is to carefully choose topics that are appropriate for students of certain age groups and will acomplish certain goals. For example, if an elementary school teacher wanted to teach algebra, he/she would do so using materials catered to elementary school aged students, not high schoolers.

-

Curation readings