Commentary

-

Zidane - Database

A New Post

I thought this reading had an interesting viewpoint. I’m not sure whether it was written in the 90s or closer to the current day, because it switches points of view sometimes (going from talking about the Razorfish visit in the present tense, and then moving to reflecting on it). Upon reflection, it seems like it is the latter option. I was confused however, because I’m not familiar with the timeline of how workspaces began to transform from the traditional cubicle setting to more of what Razorfish has been doing. At the start the narrator was describing the discovery of Razorfish’s workspace as a futuristic and uncommon one, while from my point of view, it was simply a modern workplace. However, the fact that he was reflecting on this experience and still saw it as new created some confusion. I thought it was interesting when the author said, “If with GUI the physical environment migrated into the computer screen, now the conventions of GUI are migrating back into our physical reality.” This was interesting, both because I’ve never thought about work spaces like that, even though I’ve worked in a start up that is laid out very similarly, and because It reminds me of Augmented Spaces. It’s not the same as those - they hadn’t integrated any innovative new technology into the spaces - but the idea of modeling digital spaces after physical spaces, and then later on doing the reverse is shown in both. It was also cool how they linked this to other real world institutions of their age - how libraries and museums were being replaced with computer databases. However, it was not necessarily a complete migration as we still have those (newly augmented) spaces. [Side Note: I noticed that what he mentioned about computer spaces, specifically using 3D navigable space to display the semantics of human language was very similar to a project happening in our class with the 3 boards] It was interesting how they used a video game to talk about how narratives have been presented as continuous navigation through space, specifically Tomb Raider. This has become commonplace in not only (the majority of today’s) video games to a huge degree, but also physical entertainment experiences , like themed roller coasters (i.e. pirates & space mountain at Disney world). One point I didn’t agree with was how the author attempted to reverse the assumed roles of informational and spatial communication. They said, “For instance, the user navigates through a virtual space both to work and to play, whether analyzing scientific data or killing enemies in Quake.” I don’t really think this negates the innate association of work with text, and entertainment/media consumption with spatial/graphic representation. Maybe if they pointed out that text-based adventure games existed, as well as 3D software for different types of work. But abstractly comparing a realistic, 3D world in a video game to the GUI usually found on a desktop doesn’t really do much for me. When the author introduced the two goals (essentially creating interfaces for processing information, and creating a way of navigating spatial representations) I thought it was interesting how he related them, in that they were extreme ends of a spectrum tat one should strive to be in the middle of. However, when they used search engines as on a far end of the spectrum, claiming they want to “immerse” the user in its universe to prevent them from going to other sites, I was less satisfied, as the entire purpose of search engines is to find other sites. Maybe if they argued that Google, for example, has added numerous features to immerse the user in the improved and expanded functionality of the base search engine in order to prevent them from using other search engines, I thought it would have made more sense. -

The Language of New Media

Manovich describes and is able to put into concrete ideas what I have always kind of thought about the world with respect to media and computation - being the general idea of data and algorithms being like the most basic unit/building block of media and underlying everytihng. Especially because I have always been surrounded by very technical people while I myself do not have the “coding” gene, I have always marveled at how people are able to deduce problems into matters of numbers and algorithms. In a way I always thought of it more in the reverse of Manovich’s description, that all these large and complex forms of media and programs can be broken down all the way to the level of data input and algorithmic output, whereas Manovich kind of walks you through the idea starting with the data and how they work together to then build up to the final image, program, game, etc. I especially like his constant use of examples to support his ideas to make it a lot more relatable and easier to understand these super conceptual ideas he’s putting forth (especially the whole section on video game narrative). Another one of the most interesting topics to me was the idea of the interface being a more recently introduced, third element to exist that connects what’s going on behind the scenes versus what’s going on with the user, and therefore has a lot of control to affect the user outcomes.

-

The Language of new media | The form

Manovich’s approach to GUI (Graphical User interface) is interesting in the way he describes it as a circular pattern where there is a migration into the digital realm for the last period of time while recently there have been a bridging back into the physical reality manifested through AR/VR and all the Human-Computer interaction platforms.

He stresses out the importance of the use of computers as a medium used both to execute work tasks and leisure/gaming activities. The parallelism he draws between description and narration and then again between narratives and databases is insighttful. Actually nowadays a lot of importance is put to the aesthetics and the representation medium(description)which might at some point overwhelm the information conveyed(narrative). This mainly manifested through the communication medium used in web interfaces .

Databases being in their nature a collection of data follow a specific logic from gathering to storing and indexing. While the web is an open platform that keeps on growing, Manovich points out how this feature puts webpages under the collection title rather than a narrative.

While the simple assignement of a task for the player within a game(winning, killing the monster, achieving a high score…) pushes the interaction into the narrative realm. Games are by nature governed by algorithms where as Wright explains the repetition of the experience turns into a loop building between the human mental model and the computer model.

-

Database: the forms

As the world still appears to us as an “endless and unstructured collection of images, texts, and other data records”, it is only natural that we should seek to collate them in a ordered manner and that results in a database.

The idea behind a database to help us make sense of the world, but being a jumble of separate things, it perhaps has less appeal that the cause and effect nature of narrative to which we are so accustomed.

The database represents the world as a “list of items” but refuses to order that list for us in anyway which can become confusing and frustrating when we have a tendency to depend on things evolving in a linear fashion. The idea of a database of information works against our notion of time.

Manovich argues it’s simply a matter of finding the right ‘algorithm’, the right way of reading a database for it to become as normal to us as narrative.

-

The Potential of Spatial Humanities

It seems that the disadvantage of using GIS in the context of the reading is that it it ignores the relations that take place in mapped places. It is purely technical with its data and so poses a challenge when trying to use the technology with the humanities. Also, it can be expensive and hard to learn, both crucial aspects that can drive people away from using it. In terms of advantages, it provides useful data that if used properly and extrapolated, can answer many fundamental questions about the area in question.

-

The Poetics of Augmented Space

One of the most interesting points made by the article was the evolving relationship between architects and augmenting space technology. The author gives examples of how architects are redesigning their spaces to allow technology to work with them. The author shows how one architect followed a more radical approach with his spaces and how he integrates technologies such as computer controlled lights. He eliminates all straight surfaces and angles. This can be very important since technology used to augment spaces can greatly benefit from easily mutable spaces. This added variability aligns with how data in the augmented spaces can be constantly changing in time and space. I believe many museums can learn from this in how they design their spaces since if they make them too fixed it can hinder future creativity within them. Now thinking about the MFA after reading this paper I can think of some areas in the museum that seemed like they would never change, one example I remember was a curved slim pathway with paintings on the curved walls. The nature of it being curved and narrow makes it impossible to change and since not many people fit through it one cannot do much with it apart from sticking art on the walls.

-

The Chartjunk Debate

The main argument of this paper was that adding irrelevant “junk” information to graphs is not at all that useless. The researchers argue that even though the data in some graphs may not be organized in the simplest and most efficient way, they help readers remember the main takeaways in the long term. This may be true for graphs designed for users that are not experts with the topic at hand, such as those described in the paper that appear on newspapers. These type of graphs may even need to be presented in such manner so that readers would actually be interested in reading them. Graphs that are used in the workplace on the other hand need not any of these embellishments, since they are meant to be read by people already familiar with the topic. This research however made too many assumptions by only studying cases by a very small group of people. To be able to show trends they need more people from different backgrounds as well.

-

Museum Curation

The articles describe how museums have shifted from having their focus on just objects towards the relevant society’s relationship towards to those objects. I believe that this should be the main focus of museums, they should strive to foster discussion and educate people.

The second article talks about how many museums have had to integrate technology into their collections to make experiences more immersive to the public. This is probably true since we live in a society where even little kids have phones and when they go to a museum they can get easily tired of objects and text. I think it is important to use technology wherever appropriate to provide different experiences but museums should still keep in mind their main goals. Many museums take a different approach and overly use technology to make it more fun to the general public. Even though this is innovative, too many such distractions can make museum users lose focus on the stories the objects are trying to say, since they would have much of their attention on the technology itself.

-

Layering and Separation

Tufte’s main point in this chapter is that layers of information in designs need to have a certain degree of separation and communication between each other to cleanly present the data. Clustering and boldening can remove emphasis from the main argument of the design and so an approach that focuses the reader on the relevant information is essential for these models. He argues that failure to do this lead to cluttered and incoherent displays filled with disinformation, which will visually distract the user.

-

Deceptive Visualizations

This paper discusses how data visualizations can be deceptive. Such data is presented in a distorted or exaggerated way causing the user to believe a different story than the real one. The study presented in the paper showed that a significant portion of the participants got tricked by the graphs. I have seen a lot of the techniques, such as distorting the axis, on the television, which plays a large role in manipulating people into believing something that may be true or not. The power from such manipulations comes from the fact that most of the population do not spend time analyzing a graph. They just look at the visuals to notice a trend, size difference, or steepness in lines and get a clear message from it rather quickly. The study was not able to provide with a definite answer to the correlation between individual cognitive abilities and the individual getting tricked. Even though this probably plays a large role, many smart people read a graph fast and do not spend time deeply analyzing both axis, checking the scale factors, etc. In a fast paced world, simple deceptive visualizations can even fool the smartest individuals.

-

Database Commentary

This article mainly discussed the relationships between database and narrative. It talked about how the user of a database traverses it and then gets a narrative from it. I liked how these interactions were described throughout but did not like how things like the internet were analyzed in terms of narrative. For example, I have no problem with the internet just being a massive collection of items that may or not be related to each other. Unless a specific narrative is explicitly given by a medium, in cases such as the internet it makes sense for the user to make his own narrative. The author described the relationship between databases/algorithms to tangible actions and objects. I do not think we really think about these sort of relationships when we read the news, watch a movie, study for an exam, etc, but doing so can potentially lead to gaining a deeper understanding of our surroundings.

-

Case Studies

Augmented Objects

The Project being built on collection from the memory of the Jewish community while manipulating them in an augmented reality setting presents a rich perspective where the different artifacts are read in a continuous narrative to be displayed in an authentic setting in order to draw a more comprehensive meaning for the objects.The approach presents of course many challenges in the execution specially in relation of a high resolution in conveying the actual feel of the period of time these objects belong to.

##Virtual Reconstruction

The virtual reconstruction of a refugee camp is definitly a challenging process, however very problematic, it might also lead to infidelity in conveying some features which might affect a lot of the misconception already built around these spaces. However, I think that the intent of bringing this experience for people who otherwise will not go inside a refugee camp would be an educational in the aim of bridging the gap and overcoming racism.

-

Museums as a Discursive Space

Kreps discusses object- and people- orientation in curation and how they go hand in hand. She argues that the museum experience cannot be just one or the other, but rather an “interplay of objects, people, and societies” and their relationships, all considered in the context of society and culture, since individuals experience objects from different perspectives based on their social context. Jana further proposes the idea of museums being a “discursive space”, where negotiation, debate, and discussion are invited, acting as fields for action that the curator has the power to dictate. This is exemplified by the recent movement away away from the “blockbuster museum spectacle” and towards more individualized meaningful exhibitions that connect to visitors’ senses, emotions, identities, and interests. She calls for museums to be more cognizant and inclusive of a wide variety of identities when curating experiences for visitors, which she even calls “users” rather than visitors. I think the overall movement to make museums less object-focused and more people-focused definitely enhances our consumption of them, as should be true for designing any kind of experience (i.e. architectural, product) - the more you keep the final user in mind when creating anything the more engaging the experience. However, there is definitely a limit to which this can be accomplished, and it is much more challenging to accomplish, given that such wide ranges of cultural and societal contexts exist that cannot possibly all be considered. I personally feel that the MIT Museum is an example of a museum that does not totally successfully accomplish this engagement with its visitors - with visitors form such a wide range of cultural and intellectual backgrounds that come to visit ‘world-famous’ MIT, I feel that the museum’s exhibits do not a great job of fully “onboarding” its users because they can be quite technical and difficult to understand, and do not engage with all ages and kinds of users equally.

-

Museums and curatorship

I think it is great that objects, and the value of objects, are diminishing in significance in the museum space. As Kreps points out, the traditional object-oriented approach to museum curation creates problems in decontexualization and also in provenance. The question of who rightfully owns these objects can be quite murky. For example, even today, the Greek government is still trying to reclaim the Parthenon marbles, half of which were looted in 1812 by a British earl and are currently property of the British Museum.

The Museum of Broken Relationships, originally a travel exhibit before finding homes in Croatia and Los Angeles, innovates as a social practice by collecting objects donated by visitors (or “users”, as Macalik would say). The museum was borne from the curators asking their friends for relics of past, failed relationships, and eventually expanded to asking visitors for their objects, whether they be images, documents, physical keepsakes.

I love how the Museum of Broken Relationships challenges traditional curatorship by collecting objects that are not rare, aesthetic or particularly valuable. What makes these objects worth collecting and what draws in visitors is the story behind the objects, why they were significant to someone in the world. The context is everything. The objects, often, are just everyday objects that are not expensive or extremely unique. The museums encourages discussion and reflection not only on the fragility of human relationships but also on the political, social, and cultural circumstances surrounding the stories being told. The collection respects the audience’s capacity for understanding wider historical, social issues inherent to different cultures and identities and provides a catharsis for donors on a more personal level.

As for being a discursive space, I am also glad to see a shift to promoting museum-goers as equals in power and importance with the institution of the museum. If museums are, as many claim, serving the public, they should reflect the needs and life experiences of the museum-users. And in order to do that, users need to have some way of providing feedback or contributing to the museum curation.

That said, I’m not saying museum curatorship should be a democratic process. Rather, there should be balancing of the current hierarchy in museum management to give museum-goers/users more say in the preservation of their cultural heritage, history, and understanding of the world.

-

Museums and Curation

Christina Krep Reading:

Role of the curator is constantly evolving. Museums are now more concerned with providing an educational experience for visitors than it is with the actual objects within the museum. Curating has evolved into a people and socially-oriented field of work just as museums have evolved into such.

There’s a debate on whether museums should be people or object focused. I think there’s room for both to shine. Similar to Krep’s point I believe that these two concepts are not “mutually exclusive”. Instead there should be a call to action to encourage curatorial work that highlights the “interplay of objects, people, and societies.”

“Curating as a social practice.” Meaning that individual societies have patterned ways of seeing, valuing, and ascribing meaning to and treating objects. This point leads me to believe that the way we experience and engage with art is biased. When we frequent museums, we are doing so through the lens of the curator. Therefore, understanding the curator’s background is essential to understanding how you’re experiencing museums.

I appreciated Krep’s point that in Western museum culture, the “social value” of objects recede into the background once they enter museums. I have been in a many of museums whose sole focus was the uniqueness or rarity of an item instead of its historical implications.

However, museums have shifted from being defined by their relationships with objects, towards their relationship with visitors. Curators should make an effort to involve those cultures whose artifacts are a part of their collection, in an effort to not offend them. Furthermore, the shift in how we define museums has moved towards defining the curators relationships to those people represented in their collections.

Jana Macalik Reading:

Discursive spaces are defined as spaces that foster negotiation and debate. Museums serve society best when they are founded on the principle of intentionality. I like the notion presented to challenge the use of the term “visitor” when speaking about those “users” who explore and engage with the museum itself. “Visitor” implies that those coming to the museum are being hosted and therefore the objects found inside hold weight that supersedes interaction with said objects. This brings me to my point that my most memorable museum visits have been those where I am the engaging with the artifacts and feel a deep connection to the items in the museum (culturally). An example of this, was my visit to the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C. In this museum they provided users with a wide array of explorative and immersive experiences. One of my most memorable experiences was an exhibit that gave users the opportuinty to record a video based on prompts that relate to the African-American experience.

-

Museum and Curation

In “Curatorship as Social Practice”, Christina Kreps suggests that museums has shifted their focus from the objects being collected to the relationships between objects and people, as the role of curators expanded. In “Introduction to the Special Issue: Discursive Space”, the authors take a step forward to argue that museums are spaces that “foster negotiation and debate, polarize and politicize space, and invite discussion fraught with contradictory views.” Under such situation, “visitors” of museums will become more like “users” so that the power dynamic can be changed. Besides, they advocate users to publish their museum experience on social media, as a second selective curation.

A positive example of that is the the American Museum of Natural History. In the “Unseen Ocean” exhibition, the curators are using a lot of different technologies to make the displayed objects more interesting, and the experience more immersive, especially for kids.

Unseen Oceans Exhibition at American Museum of Natural History

Harn Museum of Art provide a “Instagram frame” to its users in order to encourage them posting on their social media, both as an advertisement for the museum and a selective curation of the arts.

-

Digital_Humanities Commentary

Case study 3:

There are a lot of interesting details to consider in this case study, especially in regard to the unstandardized documentation methods of all the religious artifacts. The amount of complexity involved in both collecting and validating the information is remarkable, especially with the recordings of private religious practices. How do you preserve sanctity and respect for the culture while making it vulnerable and open to interpretation and observation?

Case study 4:

I like that the case immediately talks about “the idea of using a virtual reconstruction…touches many nerves.” I thought the same thing right before reading the sentence. This case presents some unique challenges because it is deliberately not a display of collected artifacts, but instead a careful reconstruction of a site. Ultimately, its accuracy and impact is largely in the hands of the artists who interpret the information collected about the site— interviews, images, testimonies. I am particularly curious how they will integrate multimodal data into the experience and what they decide to prioritize in terms of the experience.

Case study 5:

The diversity of the types of manuscripts and written information in this case definitely lends itself well to the idea of a “multidimensional essay.” I often get frustrated whenever I read purely textual analyses of multimedia pieces and experiences— it feels like it’s “down sampling” in a sense. However, this project team handles these discrepancies very well, not only in their media and presentation of choice, but in their choice of team members and prioritizing complementary and diverse skillsets. I also particularly liked that the first point of the work plan is that the ENTIRE team works together to develop the information architecture— rather than immediately dividing work between siloed teams.

-

Curatorship as a Social Practice + Museums as a Discursive Space

The question of the role of a museum and the role of a curator highlights an idea we have discussed extensively: given data (in this case, museum objects), tell a story. Kreps comments on how the specific role that a museum plays has changed over time from one of simply presenting collections of objects and information without commentary to telling a narrative with these collections. This transistion parallels the commentary on the role of the library as an institution. Previously, the goals of a museum and a library were similarly making information available to the public (although the museum’s information is curated and the library’s is not). With the availability of technology to allow people to access nearly any information electronically, these roles have had to shift. The museum’s focus must also be on its “users” as Kreps calls them. In particular, as captialism has extended its influence to museums, the users now carry even more power in their ability to provide funding for a museum.

This power can be taken to an extreme. The Museum of Ice Cream, and other pop-up museums like it, exhibit the extreme of focusing on making a museum an “experience” for the user, ignoring the importance of anything else. These provide their visitors with a visually enticing Instagrammable location, but do not provide the visitor with any new information. Arguably, they do not even achieve their goal of making an experience, as there is no story behind oversized plastic popsicles; it solely exists as a “pleasing” image.

This is where Jana Macalik’s discussion of making a museum a discursive space is important. Kreps touches upon this, as the role of the curator can be to counter the users’ traditional beliefs. The Enemy at the MIT museum was clearly a good example of this, but as this was already discussed in class, I can comment on another exhibit at the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago called Extreme Ice. This exhibit shows photos and videos taken at the poles over the past ten years as a dramatic visual representation of climate change. Its clear intention is to serve as a call to action, and to influence people to care more about this pressing issue facing us. This is explicitly stated a number of times throughout the exhibit. By creating this exhibit, the museum hopes to exert real change to an existing problem by spreading awareness about it. The exhibit is perhaps a more specific example of a discursive space, as it is less about starting a discussion and more about increasing awareness.

-

Comments on Case Studies 3-5

All the studies look at projects that aim to digitize and exhibit physical information (that is, objects, buildings, sites and other inherently non-abstract things) to a wide audience, while being careful to do so accurately an in accordance with the wishes of those originally associated with with what is to be exhibited. This is no small or easy task, and it is interesting how the different projects approach it differently, both using different tools and aiming for different platforms.

The projects, especially the “Augmented Objects & Spaces” and “Virtual Reconstruction of and Afghan Refugee Camp”, face interesting dilemmas regarding how much to display of the available data, and how to do it in order to present a nuanced, factually correct view without disregarding subject privacy or sensationalizing the experience at the expense of the content.

As the case studies do not include any reports of how well the projects went, and the descriptions are fairly high-level, it is difficult to point out any appearent major flaws or strokes of genius. If done well, though, I believe they all have the potential to expand upon our knowledge in the relevant fields.

-

Commentary

Curatorship as Social Practice vs Introduction to the Special Issue: Discursive Space

Both texts describe how museums are nowadays reflect more the connection with culture rather than focusing on the actual itself. Curators are not anymore simple care taker of the artifact but actual designers of stories and narratives building up for an educational experience.

The actual artifact is not anymore treated as a freestanding object but more of a social construct. Cash Cash’s argument in relation of the curatorial world as a direction for people’s orientation. The general predominant idea of decontextualization of the object to be displayed in an environment outside the culture where it belongs in order to fit within the frame of the museum to be displayed in is stripping a lot of the conceptual strength.

This decontextualization of artifacts creates conceptual distance between the object and the people actually going through the exhibit which transform the experience into a skimming activity rather than an immersive activity.

This fact is actually mostly experienced with a lot of the historical artifacts that are exhibited especially when they are displayed outside the culture where they belong to.

The concept of “Discursive spaces” as platforms for social dialogue, aligns with the shifting of the role of curator towards provoking educational insights in launching this discussion.

One of the latest exhibitions I visited was at the USS Constitution in Boston where the main experience involves visiting an exhibition space in addition to the boat. The main exhibit was mainly built around the actual making of ropes around the boat. I think that the fact of focusing on one element and dive deeply in the making process why explaining the relation to the life on the boat is an interesting approach.

-

Case Studies

Case Study 3- Augmented Objects & Spaces: Jewish Ritual Objects in Diaspora:

This case study takes in to account the provenance of the objects in the museum, which I find to be especially important. You cannot truly understand something or someone if you don’t understand the origin of it. In this sense, provenance is crucial to preserving the artifact’s cultural and historical implications. I also appreciated that the museum sought to bring in the people whose culture is being displayed so that they can understand how to best or showcase (or not) certain artifacts that were obtained “surreptitiously”.

Case Study 4- Virtual Reconstruction of an Afghan Refugee Camp as a Site for cultural memory:

While this virtual reconstruction of an Afghan refugee camp is unique, its focus on reinventing traumatic experiences for users brings up many questions for me. While I realize that the purpose of this virtual reality immersive experience isn’t solely to reinvent traumatic experiences of those who endured these camps, I could not help but keep that at the forefront of my thoughts when reading this case study.

Case Study 5- Multi-Authored Locative Investigation of the Zenon Headquarters and Corporate Archive

I believe that if done right, this project can be scalable and translated across a multitude of historic buildings with rich history embedded in the architectural landscape. The most fascinating part of this project to me was having to take something physical (augmented reality) and turn it into an experience that off-site visitors could also enjoy. This addresses the notion of accessibility within the field of Digital Humanities in a way that I sometimes feel is overlooked. I appreciated the call to action to allow those interested but unable to visit the site, the opportunity to explore the archive in a unique way.

-

Museum Response

A New Post

In Kreps’ article, they speak of a shift in the “goals” of museums. It talks about how they, both the museums and curators, are no longer focusing on collecting objects for the sake of having a collection to display, but are focusing on striving for more of an educational role, and using said objects to reach that goal. Most of the focus in the article is on how the role of the curator is changing with the times. On how the work of a curator is seen as a social-practice, and how that work changes as the relation between objects and humans changes. It’s also interesting that they note how if curating is a social practice, then it follows that curatorship in different societies is unique.

The current ‘state of operations’ for museums that the article is arguing for a departure from involves decontextualizing of objects. Museums currently take objects from their social settings and decontextualize them, or give them a new meaning outside of their initial one, inside of the museum context. They argue against this act, because it creates a disconnect between the people and the object - it is only understood as a “special artifact” and not in the correct context. Also, another point they bring up that is really important to me is that this neglects the cultures it takes from at the least, and at the most, it disrespects them. This change is good because it’s important that the museums give the necessary respect to the cultures they are using to profit.

The Macalik article goes into slightly more detail on what these museums should be moving towards - Discursive Spaces, being “spaces that foster negotiation and debate, polarize and politicize space, and invite discussion fraught with contradictory views.” The main focus of this article, is about how museums (and curators) ought to be more fluid with their purpose than they currently are, by transforming themselves from an object display house, to a more discursive space. They also made the point that in order for the conference on this topic they had to have relevance, they must have relevance not only to the museum community and other curators, but to the users that populate them as well - a great point. However, I’m not really sure that the current mode of being for museums doesn’t take relevance to users into account - each museum has it’s own category / niche (museum of fine art, museum of science) and users know what they’re getting themselves into when they go to these.

There was a portion of the article that mentioned a change of referring to those who frequent the museums from visitor to user. At first I didn’t really understand how changing the syntax of the same entity from visitor to user changed anything about the actual practice. Curators can still dictate how materials are perceived by guests, regardless of whether we say they’re using or visiting the museum. however, reading further I understood what they meant.

A problem I had while reading these articles is that while I think it is a very interesting movement to provide a more personalized experience for each user that curators have less of an absolute say in, they don’t really go into detail on what exactly that means. It’s easy to make the connection that augmented spaces from out previous discussions can be a good way to implement these values - but what exactly would the content of these new museums be? They don’t give any concrete ideas as to what these experiences would be, and while they make a convincing argument, I don’t really know where to go from there.

Enter text in Markdown. Use the toolbar above, or click the ? button for formatting help.

-

Comments on The Role of Museums

Generally, I think the change from object-centered to user-centered methodology is a welcome change to museums, as it has been in other areas - notably the tech industry with the advent of human/user centered design. It makes museums more accessible, hopefully making it easier to spread knowledge to, and spark interest among, the general population.

By subsequently moving beyond what Kreps suggests, and into the realm of Macalik’s ideas of the museum as a discursive space, it is also possible to engage the audience further by facilitating debates between both different external persons, and between the public and the museum itself. This, however, is a move I view as more risky, as it requires a more educated audience than simply a narrative exhibition. It also assumes audiences want to participate in a discussion, something that I would consider far from given. It is a very interesting directioin for museums to go in, though, and I would be excited to see what sort of experiences strategies like that can result in.

Finally, I also want to express how important I think it is that this new direction expands upon, not replaces, museums’ roles as specimen colletions and time capsules. The fact that interactivity and discussion can make knowledge more accessible, doesn’t mean the origins of the knowledge are no longer important. (Though I am not too concerned about this.)

-

The Poetics of Augmented Space

As Manovich discusses in his article, there are many ways in which a space can be augmented with information, with various degrees of personalization. The “simplest”, and most common way of augmenting space, is in a way what humans have always done; adding extra information to architectural surfaces through paintings, inscriptions or, more recently, screens displaying dynamic imagery. What characterizes this form of augmentation of space, is that everyone will have the same experience of, save for personal associations or varying connotations, and agree upon, what the space looks like. The next, and increasingly common way of augmenting space, is agumentation that is customized for each user. This is however no small category, and comprises everything from public devices with input mechanisms, to personal AR technologies.

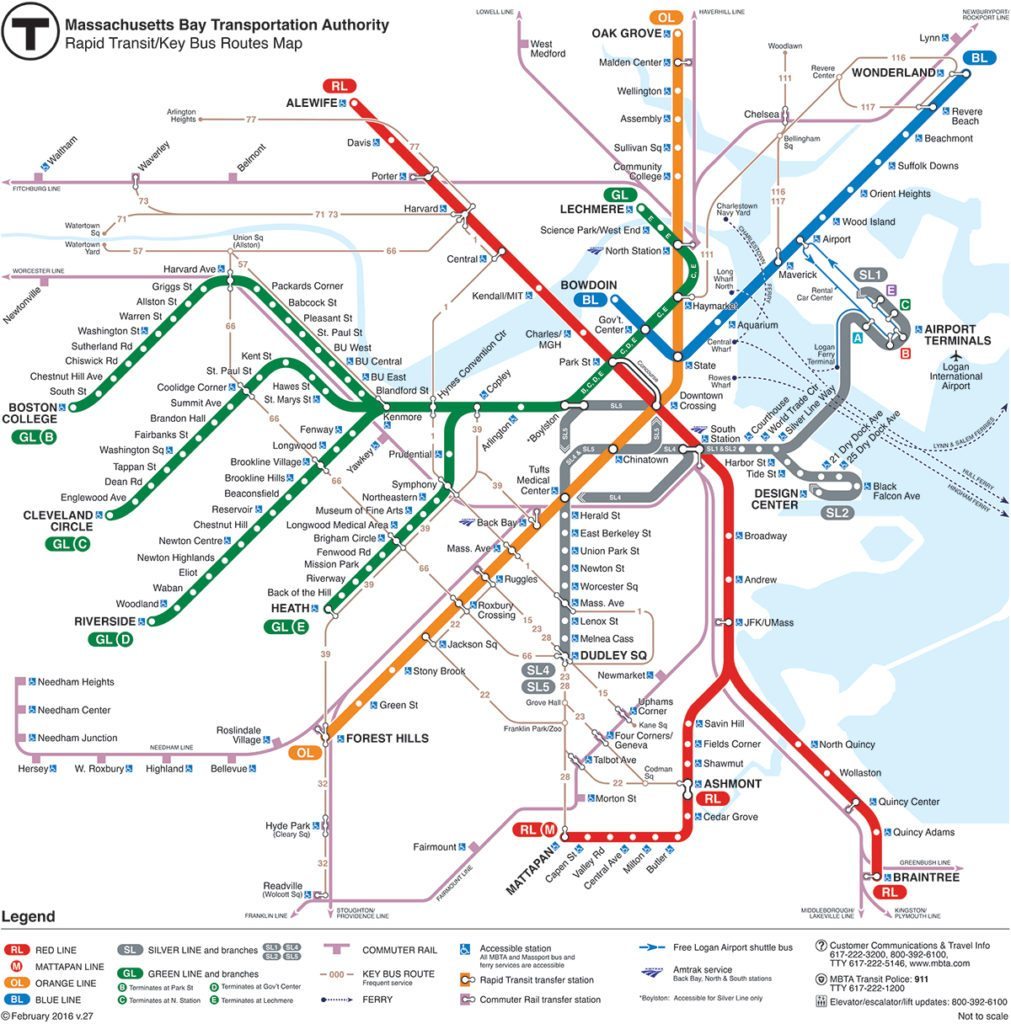

In the Boston Public Library, Space is augmented in three main ways. The first is through books, that while arguably less accessible, or at least less in your face, than large, electronic displays, is definitely information distributed in space. It was also very expected of a library.

The second is through electronic information boards, where one could explore the library’s colletions and delve into the items’ metadata in addition to digital representations of the items themselves. None of the electronic information displays we found, did, however, work properly, which rendered us unable to assess the value and usefulness of a working system.

The third was through personal computers for people to use for web browsing and document writing. This was the most personalized augmentation in the library, as the computers seemed intended for single users, as opposed to the information boards, that could equally well have been used by small groups of people (had they worked).

There were also some more outdated pieces of hardware, like several microfilm magnifiers and scanners, though these were more hidden away and not in use by anyone.

All in all, the library was not particularly successful in augmenting the experience with advanced technology, instead serving as a space for people to use personal computers, an activity so generic I would say it doesn’t really augment a space as much as it makes the space irrelevant, and occationally reading or researching books.

However, whether this lack of augmentation is actually a negative thing is a discussion completely skipped in Manovich’s article. He doesn’t discuss the implications as much as he is simply fascinated with the possibilities, which I feel provides a somewhat shallow analysis of the situation. Especially with the recent focus on both privacy/surveillance and online, isolated groups/echo chambers, I am personally concerned about the extent to which spaces should be further augmented, at least as we move in the ever more personalized direction. While I definitely agree that augmented spaces are cool, and could have the possibility of streamlining our lives for minimum cognitive load (or of course maximum if you so choose, but who will realistically choose that?), I do not think ultimately risking a shared reality is worth it, almost no matter the benefits.

Exactly how this will be solved is of course a different matter, but being blinded by shiny, new technology is definitely not the right way. We need an open, enlightened debate about this, before we’re at a stage where “big brother” knows everything and curates specific realities to each and every one of us.

-

The Poetics of Augmented Space

In his essay Lev Manovich talked about the increasing existence and importance of “augmented space”, which he defined as “physical space overlaid with dynamically changing information”.

I totally agree with Manovich’s statement that the high-tech society is featured by the close connection between surveillance/monitoring and assistance/augmentation. The concept is illustrated in some of the interactive art installations at MIT museum. One example is the staircase that can sense people’s movement and play music responding to the movement, where the kinetic sensing is a form of monitoring, and the music is the augmentation. However, like most of the other installations in the museum, it doesn’t have the ability to gather more information about each individuals, therefore can only offer an universal experience to everyone. One potentially improvement, according to Manovich’s theory, is to ask all the interactive installations to collect more information about the specific user’s demography and preference, and provide a tailored experience based on that data. The improvement, however, is associated with even more surveillance and monitoring. In the essay, Manovich also talked about the transition in how galleries display work: from placing two-dimensional objects on a wall to using whole 3-dimensional space of a gallery. In the “Lighter, Stronger, Faster” exhibition that showcases marine design and engineering, the exhibition space is partitioned corresponding to the size of the drawings and physical models. In the “Advanced Visual Studies” exhibition, one of the artwork is a cubic dark room with moving lights projected to all directions, which allows the visitors to actually occupy the artwork.

Lastly, Manovich suggested that architects should take augmentation into consideration and integrate it into the design. In the case of the MIT museum, however, augmentations are always changing as the exhibitions are changing. What the architect can do is probably provide a “white cube”, as a canvas for the artists or exhibition designers.

-

The Poetics of Augmented Space

Manovich describes many more techniques than what we observed in our Ethonographies of Public Spaces activity that could have greatly enhanced the experience. While we did observe some of the paradigms of information technology that Manovich highlights, there are many that the MIT Museum lacked and could have benefited from. Of the technologies the MIT Museum did exhibit, the most prevalent was probably tangible interfaces - bringing closer the human to the computer in HCI by employing physical space as part of the interface. Touch screens and other tactical exhibits were plentiful throughout the museum (i.e., interactive staircase playing music with each step). On the same hand, ubiquitous computing, intelligent spaces, context-aware computing/ambient intelligence, and sensor networks all go hand-in-hand to help make tangible interfaces possible.

However, the museum does not go far beyond this, not employing much of any cellspace technologies at all which is a large component of Manovich’s essay, or wearable technology, augmented reality, or building intelligence. And what the museum does employ is in modest, not highly immersive, engaging, or paradigm-shifting, with interactions brief and limited in scope and scale. I think what the MIT Museum could probably capitalize on the most would be in building intelligence, since there seems to be a lack of connection / harmony between the contents of the museum and the building itself. Exhibits seemed somewhat arbitrarily tossed into the spaces and I felt, as a visitor, that I could have been better oriented and more engaged with the space if it were better at “fusing” building and exhibition, as described by Ineke Schwartz (p. 234).

The museum also incorporates a now interesting mix of “white cube” and “black box” displays, with spaces littered with small black screens as well as large projected surfaces. While this may have seemed compelling and innovative at the time and to an average museum-goer, it in retrospect seems almost amateurishly motley, given Manovich’s comparison of the two.

Black Box Versus White Cube example

-

Museum of Design Atlanta

This weekend I was in Atlanta! So I went down to the MODA and see what they had on exhibit.

One of the coolest parts of the space is that it caters to basically every age group but emphasizes being a creative space for kids. 3D printers and workspaces greet you at the door, directly adjacent to exhibits themselves. It’s inviting and makes design seem approachable to even people outside of design. I brought three of my friends with me– all of which are not in design fields, and they had a blast.

I was expecting some more interactive stuff though. There wasn’t that much, mainly just some displays, but nothing touch screen or app oriented. Although, one distinct thing here was that all of the 3D models and pieces on display were completely open, touchable (carefully), and it was very easy to gather groups around the pieces. This layout seemed to encourage discussion quite a bit.

Here are some cool pictures I took from some of these open displays:

These two were from an open exhibit about a public space being built in Kenya (I think).

This was a piece of glass that only had the negative of a photo printed on it. It was offset from the wall slightly so it would cast shadows behind itself.

There weren’t really many experimental technologies implemeneted which I think could’ve made some of the exhbits more engaging, but you’d be suprised by just how much layout and interior design affects conversation. Although, I always loved the idea of having location based notes – in the same way that you can see a map of all of your photos wherever you take them. If there was a way to pin thoughts and questions to a location – in this case, MODA – I’d love to see what people have previously said about exhibits / the space. Other than that, I’m not sure if asking about having more and more social interaction is always the right question in a museum setting. Museums and exhibits can be really personal and emotional, so inserting technology into the space to encourage social interaction might detract from some exhbits. Time to go to the Cooper Hewitt though.

-

Augmented Spaces - BPL Respose

Augmented Spaces - Zidane

This is a really interesting way to describe the world around us - with many of these readings I’m learning about new ways to view the existing features of our everyday lives in a new scope. (From chart junk to deceptive graphics and now to Augmented Space). In terms of the library, I saw many examples of augmented space right when I entered. There are many tv screens of different sizes that provide information about upcoming library events, staff book picks , etc. It was also interesting to observe how in the transition from the 20th to the 21st century, the scope of technological advancement has switched from providing access to virtual spaces from a stationary computer, to bringing these virtual spaces along with the user into the actual physical spaces they inhabit. Even more interesting, is the fact that the library utilizes both of these techniques - both with stationary Macs and desktop PCs that allow you to interact in different ways with the contents of the library, and the tv screens that give visitors direction.

There was a particular concept in the article that raised some concerns for me: the one where they speak about collecting a multitude of different types of information to allow a centralized program to perform tasks and make recommendations for them. The first thought that comes to mind is a black mirror episode where they take this concept to the extreme, and create an AI of a person by copying their conscience into a program, and having it perform their tasks around the house for them. While this is clearly an extreme and unlikely case, the real life example mentioned in the article has the same goals, and the means to achieve these goals involve a great deal of privacy breaching.

Conceptualizing this concept for the library. To what extent does a user need to be physically tracked through the library, or have their preferences data mined from their browsing data? It may be interesting to track their path through the library and observe how they explore different sections in order to give recommendations based on sections they might not know much about or more of the catalog of the sections they do visit. To a much lesser degree, the same information can be obtained by tracking their checkout and search history (on the library website ONLY). The first idea is much more useful in terms of the breadth of things you can actually do with the data, but how justified is the breach of personal space and privacy for that goal?

The article also mentions immersion - how you can be immersed in different ways through both augmented and virtual reality, as well as traditional ways of viewing media. I.e. video games, movie theaters. The library’s tv screens by the entrance could be seen as the greatest attempt to strive for immersion, but I personally don’t feel that they create that effect you get when watching a good movie in the theater, or when you’re engaged in a great video game. I acknowledge that these are meant to be different experiences, but I do feel like the library has the potential reach it’s own type of immersion - separate from the traditional feeling of immersion you achieve when you’re in a particularly silent section of the library engrossed in a particularly good book. It could be argued that audio books are a form of technology that the library offers that creates a type of immersion separate from the traditional form.

Enter text in Markdown. Use the toolbar above, or click the ? button for formatting help.

-

Augmented Space

Augmented Space

At the beginning of this reading, Manovich states that he “want[s] to re- conceptualize augmentation as an idea and cultural and aesthetic practice rather than as technology.” This particular point immediately interested me because I’ve only ever considered augmentation in a technical context and never as a cultural and/or aesthetic practice. Manovich aimed to show how architecture, media, art, cinema, etc. can be understood through augmentation—making this approach a fascinating one for the field of Digital Humanities. However, one point that I disagree with is the one in which Manovich declared that “augmented space is also monitored space.” While I do understand his reasoning behind it, I disagree with the dogmatism of this statement. While some augmented spaces can be reframed as monitored spaces with the intention of assessing patterns and behaviors, not all augmented spaces are created with that intentionality in mind. One instance that I see augmentation as monitoring occurs in some shopping malls around the nation. Some shopping malls use store trackers to assess and track the behaviors of their shoppers and adjust their store layout accordingly. Making the augmentation architectural in a way because foot pattern tracking allowed for the store to make data-driven adjustments to better sell store merchandise. Similar to Manovich I see a lot of augmented spaces occurring in the interior design and even retail space. Augmented spaces become a place to engage the user in its surroundings in a fashion that extends far beyond the limited view of electronic media (i.e. screens). Retail spaces currently are testing out ways to allow users to try on clothes through an augmented experience. This new reality reaffirms Manovich’s hope that augmented spaces can transcend beyond historical limitations.

-

Augmented (Public) Space

The Augmented Space article discusses how data can be layered within physical space. Prior to the technological age, this was done with mostly visual ornamentation, by adding a level of symbolism to the space. With technology, visual ornamentation can constantly adapt and animate given stimuli, and other mechanisms of incorporating data are possible, like audio tours. The question then becomes how might the idea of augmented space incorporate itself into our public institutions. The author argues that public institutions should experiment and become innovators in augmented space, rather than far behind in technology as they currently are. While I certainly agree that most public institutions are far behind the times technologically (there were MANY microfilm readers at the Boston Public Library), the reason for this is not a lack of willingness to innovate, but a lack of resources to do so, as well as a higher prioritization of the institution’s other goals. The library’s function is to serve as a public resource for knowledge, preventing it from only reaching the elite. As computers have made knowledge more and more public, the limiting factor to accessing knowledge equitably has become access to computers. Therefore, it has adjusted by providing free access to computers to the public and people who need it. While it should keep up with the times, its primary goal is to provide its users with easy access to other knowledge. Too often, attempting to “innovate” in augmented technology leads to glitchy and ultimately useless spaces. Since the library plays a vital role for people, it should not waste its time and money on unproven methods. Augmented spaces have potential, but public spaces should not be running experiments on the people it is trying to help. Rather, they should focus on implementing current technologies well.

-

The poetics of augmented space

Manovich calls for us to go “beyond the ‘surface as electronic screen paradigm’” and think of information flow as something physical, tangible, and studied just as much as the material.

I think Manovich is correct in that often, people who work with media often think of the virtual space as something separated from the physical space by a screen, or by technology. Rarely do we think of the physical and virtual space as one, an entirely new expanse Manovich calls “augmented space”.

The MIT Museum struggled to make that jump of seamlessly blending the physical and the virtual. The “black box” Manovich described was certainly on display, with a video playing on the first floor with seats facing the projector – a standard, uniform way for visitors to experience the virtual, with a clear divide between what was electronic and what was physical.

There were a few exhibits that managed to somewhat cross the divide. The stairs that lit up and played tones when a person walked across them involved both physical and virtual elements. But the physical seemed more like triggers for the virtual rather than a blending of the two.

I think blending best occurs when the virtual actively engages and makes use of the user’s physical space, rather than expecting the user to shift from the physical into the virtual. In the example Manovich gave, Janet Cardiff’s Alter Bahnhof Video Walk (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sOkQE7m31Pw), visual and auditory information from both the phone (the virtual space) and the grounds of the Kulturbahnhof in Kassel (the physical space) are blended in such a way it is difficult to differentiate one exprience from the other. They are blended such that they become one experience.

Cardiff’s piece reminds me of Yoko Ono’s work, like her poems in Grapefruit, which are written as instructions. By commanding the reader to physically do something, Ono blurs the line between the imagination and the physical world, much like Cardiff blurs the line between virtual and physical.

Poems by Yoko Ono, which augment the literary space by calling for the reader to physically do something.In Cut Piece (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-yqhSZsXIJQ), Ono breaks down the “black box” Manovich describes of performer and audience by asking the audience to cut off a piece of her clothing and take it with them. It introduces themes of vulnerability of the artist and effectively combines the space of “performance” and “audience” until they are indistinguishable.

So, Manovich’s idea of blending worlds is not a new one. But the idea of specifically blending the virtual and the physical in an augmented space, and treating the blending as a “substance” as tangible as the physical, is a novel idea, atleast for me. Drucker called for us to focus on the experiential over the material. Manovich seems to say that the two are so tightly intertwined that that we can should treat augmented space, and the flow of electronic data within, the same way we do with the material.

-

How Deceptive Are Deceptive Visualizations?

This study focused on four common techniques of distortion of data (truncated axis, area as quantity, aspect ratio, and inverted axis) that lead to two main deception effects (message reversal and message exaggeration/understatement). The line chart/aspect ratio proved to have the biggest distortion effect, which makes sense to me because among the other techniques, a distorted aspect ratio seems the most difficult to mentally adjust for, if that makes any sense. For example, it is easier to imagine/visualize a non-truncated axis, or an accurate bubble case, but harder to mentally see what a corrected aspect ratio graph would look like.

It was interesting to read through the identification and classification of different techniques was because I feel like I often notice and am critical of when these techniques are used in the real world, but I never stop to really crystallize and classify them in my head. On the other hand, while seeing these distortion techniques irks me, I also have been guilty myself of distorting data and I think it is something everyone does because we are always looking for stories out of data and we obviously want to be able to tell the strongest narrative that we can paint. However, there have definitely been times where I have tried to exaggerate my data, but as much as I try, there is a point where the data IS what it is.. Therefore, in response to the question of how deceptive are deceptive visualizations, I think you can definitely stretch the truth a bit but there is a limit to where you cannot completely “lie” or fabricate something that is just blatantly opposite/false.

-

When Maps Shouldn't Be Maps

When Maps Shouldn’t Be Maps

It’s easy to think that data that contains geographical information could be best displayed on a map. However, the problem lies in not whether or not the data can be displayed using a map, but rather should it be given the context that surrounds it? In the case of this reading the author focuses on the latter part of the aforementioned question. A focus that many more data visualization creators should take note of.

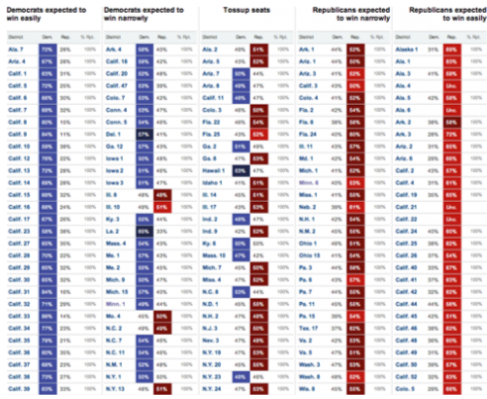

!

Visualizations like the one mentioned in the reading allow readers to gain deeper understanding of events based on additional context knowledge. Here the creator visualized which Congressional seats were most likely to go to Democrats vs. Republicans. The visualization therefore clearly shows the polarization of the parties and the juxtaposition of votes allocated in accordance with initial predictions. Now users can easily tell that Republicans gained majority of the congressional votes and disallows for the data to be easily distorted by graphing it on a map.

-

How Deceptive are Deceptive Visualizations?

How Deceptive are Deceptive Visualizations?

Deceptive Visualization effects can be classified as “message reversal” or “message exaggeration/understatement”. The study classified these effects and then rendered synthetic examples to reproduce them in a controlled environment. Results showed that deceptive charts did indeed affect the way people interpret messages and that sometimes this occurs in accordance with people’s personal traits/attributes.

I think the author brings up an interesting point when they say “not following best practices of visualization design, such as truncating the axes, may lead to a deceptive visualization either with or without intent, depending on the sophistication of the creator.” The researcher is saying that those who do create deceptive vizualitions do it either with the intent to deceive or because they lack the skillset to appropriately convey their message through these visualizations. I appreciated that they clarified that while intent is a problem area, it is not the focus of deceptive visualizations. Instead, the focus should be prioritized to the way the message is received by the reader.

“Almost all visualizations are prone to distortion or lie.” I agree witht this point because people interpret messages very differently and as a result the visualization can be painted as a “distortion” or “lie”. Also, there isn’t a one for all distortion technique one can use. Different distortion techniques–such as color deception, truncated axes, and missing labels–are dependent on the type of data being visualized and the message being conveyed. When thinking about my interactions with deceptive charts the one that is most common are visualizations than employ the truncated axes distortion technique.

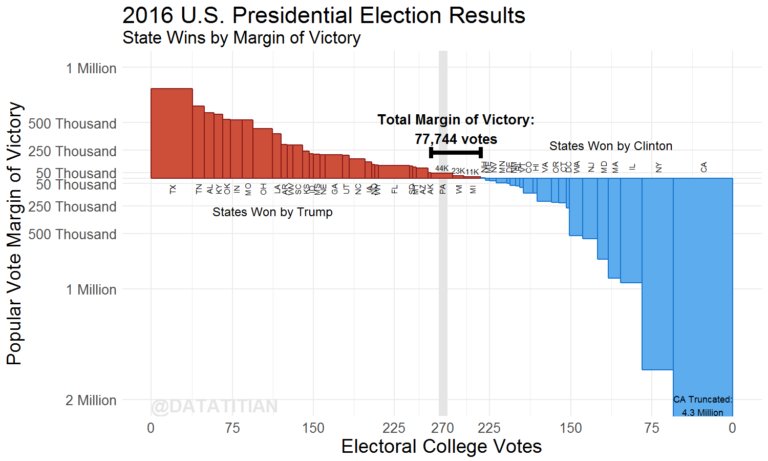

When looking for examples of truncated graphs of the past Presidential Election, I came across one that explicitly stated that some of the data had been truncated. This led me to think that if data visualizations are distorted and they explicitly tell the reader that it is–is this still a deceptive graph?

-

Commentary: When Maps shouldn't be Maps

I think Matthew Ericson has a good point here, though it is very similar to what others have expressed before: Any tool can be great in certain situations, and useless in others. What this text does is provide more concrete examples that elaborate on Bodenhamer’s “The Potential of Spatial Humanities”, showing both examples of when GIS is well used, and when other visualizations were more appropriate. Overall I liked the examples and agree with him.

-

Commentary: How Deceptive are Deceptive Visualizations?

Based on the analysis presented in “How Deceptive are Deceptive Visualizations?”, it is clear the answer is “Potentially very”. With fairly simple techniques of deception, techniques that I would say could be mistaken for simply poor graph design, the researchers were able to both understate, exaggerate and even reverse the meanings of datasets. This is of course very fun and interesting, but the implications can be dire. As suggested in the analysis, many people don’t even seem to consider that visualizations can be skewed, and thus accept the image they’re presented as accurate and true.

It is important both as a consumer and visualization designer to be aware of this, and, in my opinion, actively try to counteract these effects in visualizations we create ourselves.

-

How deceptive are deceptive visualizations?

deceptive visualization: “a graphical depiction of information, designed with or without an intent to deceive, that may create a belief about the message and/or its components, which varies from the actual message”

Throughout the article, I was thinking about whether or not all visualizations are a bit deceptive, in that we all have our own biases and personal beliefs which get projecte to our work, often unconsciously. I think the answer to that is no. I think there are some messages that are truly unbiased (for example: the population of Wisconsin has increased by 20,000 over the last two years, at an average rate of 1000 people/month; there are 15000 more words in the Old Testament than the New Testament) that can and should be visualized without deception.

I find it interesting that line graphs were found to be the most deceptive (in this specific example, and when compared to a bar and circle graph) when they are arguably the most common in the Real World and in academia. (I do not have evidence for this statement, but having read through a significant number of course 6 papers, that has been my experience.) I wonder if the simplicity of the line makes it easier to manipulate, or perhaps people are just worse at interpreting lines compared to interpreting areas.

They gave this as an example of a deceptive line graph, but I have seen graphs like this (where the axis is changed so that the slope seems steeper/lower, and fits into a graph more nicely) all the time in scholarly publications. This ties into the whole culture of “perish or publish” in academia. Nobody wants to read about inconclusive results, so people will fudge with the data a bit to make it seem like there is a conclusion to be made, even when the unfiltered data says otherwise. Of course, publishing is necessary for tenure-track postions, prestigious postdocs, grad student fellowships, etc. It is a huge problem in academia and probably at MIT, that doesn’t seem to have an easy solution without a major shift in academic culture.

-

How Deceptive are Deceptive Visualization Comments

In “How Deceptive are Deceptive Visualizations?”, the researchers first define the concept of deceptive visualization as “a graphical depiction of information, designed with or without an intent to deceive, that may create a belief about the message and/or its components, which varies from the actual message”. After that the paper focuses on two types of message-level deception: “Message Exaggeration / understatement”, and “Message Reversal”, and four techniques associated with them: truncated axis, area as quantity, aspect ratio, inverted axis. Later, the researchers conducted a case study, whose results confirmed that the four techniques mentioned before do lead to major misinterpretation.

By looking at the examples of deceptive graphics giving by the paper, I think it is a bit difficult to read the graphics without any context, and judge whether they are deceptive. For instance, I can see the bar graphic of “Access to Safe Drinking Water in Willowtown and Silvatown, as of 2010” to be a good graphic if it is placed in an article where the writer firstly presents the graphic of access to safe drinking water of all the towns with y-axis ranging from 0 to 100%, and then zoom in to the “Truncated Axis” graphic from the paper, to talk about a detailed comparison between Willowtown and Silvatown. In some way, the “Truncated Axis” method functions similar to a log-scale graph, which could be useful in many circumstances, but would also cause misunderstanding if people are lacking background information, or not looking at the graphic carefully.

-

Narrative of Space and Time

In this chapter Edward Tufte examined three major topics: the motion of Jupiter’s satellites, itinerary and timetable design, and the notation systems for dance movements

In the first part, Tufte talked about the evolving representation of Jupiter’s satellites. When Galileo started to get interested in the satellites of Jupiter, he represented their movement with simple diagrams on his notebook. In the diagram, Jupiter and its satellites were drawn as dots of different shapes. They are aligned in different sequences according to their relative position Galileo observed from the sky. Later, Galileo constructed Jovilabes with the others, and the representations of the satellites’ movements evolved from dots to continuous curves that report every positions. The representation was updated again, in the end, the Voyager spacecraft revealed the true image of satellites.

In the second section, Tufte described a series of timetables and route maps, each with its own advantages and shortcomings. He started with looking at examples of comprehensive description of a transport system requires both time and spatial experience. The map for the Czechoslovakia Air Transport Company, and the China Railway Timetable Index Page were used as good examples here of how complex network of routes and times can be shown at the same time in limited space. After discussions on timetable and train schedules, he mentioned some strategies can be used in data representation: serpentined data formations, which is especially useful when data are lognormally distributed; spilled outlying data; and end-to-end cylinder/circular graphic. I think the three strategies can be really useful on different datasets, even though they may also cause confusion and misunderstanding.

Lastly, Tufte talked about notations of dance movement, which is defined as the process of “translate human body movement into signals transcribed on flatland”. I totally agreed with Tufte that the notations themselves can be something elegant and beautiful that are independent from the motions they represent. The diagrams from Dictionary of Kinetography are almost like drawings themselves.

-

The Chartjunk Debate

Stephen Few argues a more moderate approch in the chartjunk vs. embellishment debate-well designed embellishments, when conveying simplified data, can help serve as a mnemonic to remember data, but can become chart junk when attempting to look at more complicated analyses of data.

He comes to this conclusion on the basis of a paper on the usefulness of embellishments. In this paper, the authors have 20 students look at either “embellished” charts or “minimalist” charts to compare which improved recall. They found both were equal in the short term, but in the long term embellishments do better. Few takes issue with this conclusion, as the study took what Few considers to be some of the most well designed embellishments by Nigel Holmes and pits them against poorly designed minimalist charts that even the strongest hater of chartjunk Tufte would despise for a lack of clarity. The study also focused only on graphs with relatively simple messages, as Few doubts that the same conclusion would be drawn with more complicated data. The limited sample size also skews the results-we cannot base everyone’s understanding on a few college students who likely have some familiarity with charts.

Few states the following modified conclusion from the study:

When a simple message—one that could be expressed verbally in a single sentence—is presented in a chart that includes embellishments relevant to that message, along with quantitative values that are related to but incidental to the message, then a reader will comprehend the message as well as he [sic] would had the graph lacked embellishment and will also better recall the basic subject of the chart and pattern in the data two or three weeks later, but no better soon afterwards

While Few criticizes the study for drawing broad conclusions based on a limited sample size, he does the same, drawing his own conclusions based on his own presumptions and instincts on the matter. This is not to say he is necessarily wrong; simply, I claim that Few has little more evidence for his argument than does the paper.

That being said, I do think Few’s argument has flaws. Few does state that chartjunk is too broadly defined in Tufte’s work, but Tufte has roughly the same definition that Few does. Tufte does argue that as long as it supports the work’s meaning, it serves a purpose. Few, however, includes Holmes’ works in the category of supporting meaning. However, by Few’s own admission, Holmes’ embellishments do NOT add meaning; rather, they add memory. Drawing a woman on a chart about diamonds will make you remember what the chart looked like, but it gives you no additional understanding of the underlying data. It is an artificial construct that is separate from the data, and when it overwhelms the chart, it can obscure the actual meaning of the data to one small conclusion.

While reader engagement and memorability is a valid goal, Few acknowledges that if they impede understanding, embellishments become chartjunk. In the case of Nigel Holmes’ work, they limit readers understandings to only the most basic of conclusions, and are therefore excellent examples of chartjunk.

-

The Chartjunk Debate Comments

Stephen Few argues that Edward Tufte’s definition on the term “chartjunk” is too loose. Instead of using it to label all additional decorations and graphics that don’t contribute directly to the dataset being present, people should take the intentions of the designers and the intended messages of the charts into consideration. Few also argues that the study “Useful Junk?”, which were used to deny Edward Tufte’s opinion, is not valid because of its shortcomings in methodology. I totally agree with the author that different visualizations have their own purposes and target audiences, which may be independent to the datasets they are presenting. We should take those elements into consideration when we define what are “chartjunk” and what are not. The danger is if the viewers can detect those intentions as something subjective and something that are created by the designers to express their own opinions.

-

Reading response |The Chartjunk debate

A New Post

A graph might not convey the full story in a data set but it should be designed to present the ideas in a rich way. The author examines the use of data in different scenarios whereas he tries to specify how the visual representation affects the viewer and helps in communicating the message in a more effective way. Discussing the different scenarios, on a scale ranging from an excessif embellishment to a very minimal rendering points out the importance of the designer in the choices they make to use the proper communication representation in coherence with the data used. The way Holmes’ chart introduced embellishments was not useful to convey the message because it engages the audience’s brain in a distractive way (metaphor) rather than a focused way on the data.

Moreover, Stephen Few points out a very important concept on the interrelation between the simplicity of the message and the visuals conveyed that would enable us to state the message in one sentence.This is a very important component to be taken into account while design for a data visualization because we tend to get lost in the compelling representation while forgetting the focus of the message.

-

Reading Response |Edward Tufte: Envisioning Information

Layering and separation

Effective layering of information can be challenging. An important consideration should be given to the relationship of information represented in both visual and content. Unlayered visual representation fail to communicate the ideas. A grid helps in the general reading of the information as long as it is muted and represented in a way that doesn’t overwhelm the reading of the actual data. The 1+1=3 concept underlines the importance of the space formed as a consequence of two lines and how it affects the reading.

I totally agree with the way he defines ”information” in relation to “differences” in layers and the way we separate the data that help in the reading and the conveying of the message. The cluttering and incoherent display of data can lead to disinformation and false perception from the readers specially if they are not familiar with the topic conveyed.

-

Layering and Separation

In the chapter “Layering and Separation,” Tufte explains how even complicated data need not look that way and how quality design can distill information visually into an understandable form. Tufte remarks on the following effects on understanding:

Figure and Ground

To distinguish figure and ground, Tufte recommends using color, shade, and weight delibrately and meaningfully. A mess of black lines with the same thickness conveys little information; shading unimportant things in lighter colors helps indicate where focus should be placed. When there are multiple sets of information interacting with each other-like labels for each part of a diagram-bold color (like red) can help indicate its importance. However, bold colors must be used sparingly-an abundance of bold colors against a white background can be visually jarring.*

Interaction Effects

Borders should not be the visual focus of the image-the information should. Boxes surrounding information should be enough to indicate separation, but they should serve no other decorative purpose. Using “small spots of intense, saturated color” can help increase the focus to the actual information, especially when constrasted with the rest of the image.

1 + 1 = 3 or more