An Ethnography of the Sakip Sabanci Museum

Introduction & Context

Having spent spring break in Istanbul, I visited the Sakip Sabanci Museum- a privately owned villa-turned-fine-arts-museum (a la Getty Villa). The SSM is well known in Turkey for hosting retrospective exhibitions on world-renowned artists like Salvador Dali, Rodin and Joseph Beuys. However, the permanent collection of the SSM is the home for a large collection of Islamic calligraphy art. This ethnography focuses on this collection and its display. I had the privilege to tour the collection with one of the curators, who talked me through the museums target demographic, and how they wish to expand it by incorporating different ways of information access. The museum is experimenting with various new methods – some I consider to be more effective than others.

Demographic

The Islamic calligraphy collection is somewhat of a niche interest area, and is not directly accessible for a broad audience. Additionally most of the art is in the form of old books (Quran’s etc.) that need to be well preserved and can only have one page open at any given time behind a glass display. The SSM came up with various interesting methods to overcome these challenges, and make the presented knowledge as accessible as possible. Additionally, there was a focus on making the museum interesting for children and modern art enthusiasts by introducing interactive technologies and parallels to contemporary works.

The Mobile App – A Great Way to Exhibit Books

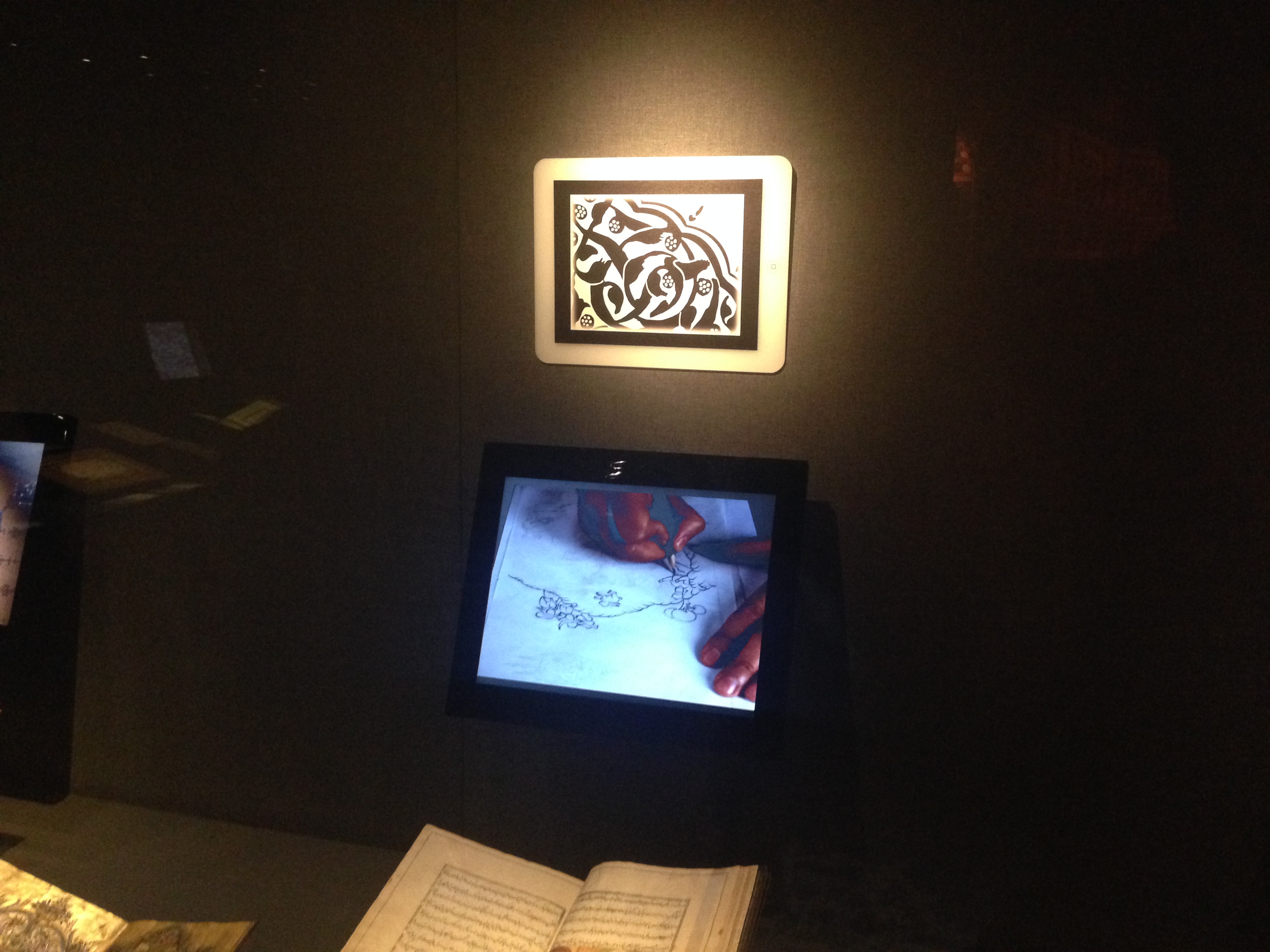

The SSM developed a great iPad app that aims to augment the museum experience with digital expansion of the physically presented information. Acknowledging the novelty of these mobile technologies, the museum provides you with the option of renting an iPad with the app to use throughout your tour experience. This can be seen as a modern take on the outdated audio-tour option. Throughout the exhibit there are markers (similar to the one below) indicating you to point your camera while the app is running:

The app recognizes the unique pattern of this marker, and redirects the user to various interactive interfaces (e.g. photo libraries, text, scans). An example application can be seen at the lobby of the museum, which used to be a living room. A pattern here takes the user to a photo library of the late owner of the villa, Sakip Sabanci, hosting various celebrities and historical figures in this living space:

But I believe the greatest impact this technology has is in its use for exhibiting books. Scanning patterns near exhibited calligraphy books redirects the user to complete scans of all the books behind the glass display. The user can pick from many books, skim through the pages, and experience the dense text as a whole rather than being limited to the open page behind the glass. This is also an amazing resource for research purposes, which is why the museum has their whole scanned collection available online.

Image of a digital book

Image of a digital book

An Interactive Table for Kids

The museum also experimented with an interactive table and large display. This installation was primarily targeting younger visitors. The table contains many “eggs” that a user can manipulate and “throw” onto the large display showing an image of the Bosphorus. The eggs then crack, and the contents ( e.g. a calligraphic boat, or bird) move around on the Bosphorus before they disappear. Although the execution was impressive, I personally found this display somewhat gimmicky, as it had no goal of conveying any form of information to the kids. Rather it seemed like its purpose was to just entertain kids that might otherwise be bored of the exhibit to this point:

A Modern Take on Calligraphy by Kutlug Ataman

The calligraphy exhibition ends with a contemporary digital artwork that reinterprets the notion of making images out of text. In this work, the artist Kutlug Ataman overlays two videos of the Bosphorus water taken from the same location at two different times of day, typing the traditional call for prayer in Arabic with one video over the other. This “dynamic” calligraphy is connected with early traces of expressionist works from Ottoman art history. The incorporation of this somewhat out-of-place artwork acts as a great gateway for contemporary art enthusiasts to engage with work that is otherwise outside of their areas of interest.